I have to admit something. For months now, I haven’t been able to finish many books of fiction. Maybe it’s because ever since the pandemic started, the whole world has become stranger than fiction. With the daily death tolls, the news itself started to read like pulp science fiction. And after the capital riots on January 6, televisual history proved far more sensational than anything dreamt up in the best political thriller. I can’t pick up a book of American fiction without feeling a self-consciousness in the prose. Either the syntax is overly decorated and flowery, or it relies on too many metaphors, or the artifice itself pulls me away. I just see words, sentences, a fabricated nothing. It feels dead, or like a taxidermized animal—not quite alive. Perhaps I can read non-fiction these days because it doesn’t have the same illusions, doesn’t suffer from the same kind of self-consciousness present in American fiction. Non-fiction is overt in its self-consciousness, straightforward about its own navel-gazing.

I need to clarify that I haven’t been able to read much contemporary fiction. I’m currently slowly working my way through several books written by deceased writers (James Baldwin and Toni Morrison) and I have faith I’ll finish them. I also have attempted and abandoned Where the Crawdads Sing twice. Maybe the third time is the charm. But the artifice is so heavy, I can’t get through the thicket of the words to fall into the dream of the plot.

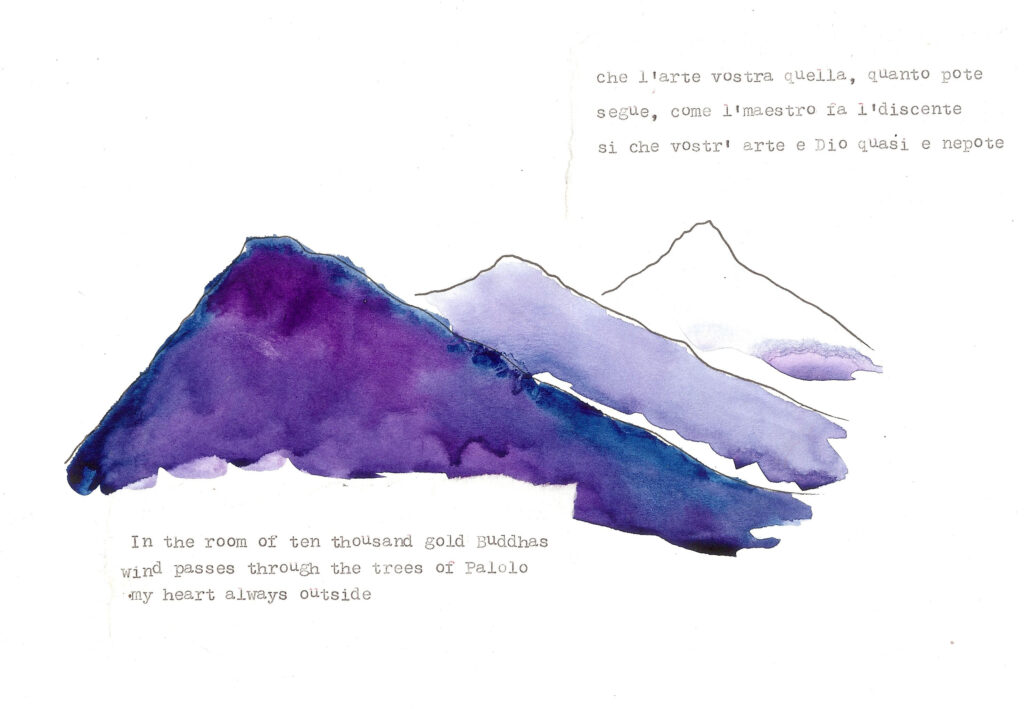

Fabrication requires a kind of self-consciousness, and perhaps we have become particularly attuned to this kind of performance, especially in our era of social media curated selfhood and self-branding. In a world where our private lives are always for sale, what’s the point of fiction? Real life often has more plot, and there’s a lot more at stake. Perhaps the thrill of reading non-fiction is the fact that some non-fiction writers have the gift of creating an intimate space in their prose, an intimacy that gives one the illicit feeling of reading a person’s private journal. Most important, this kind of feeling doesn’t come along with all the machinations and artifice of fiction. Modern fiction can often feel forced, the syntax too strained with its own acrobatics. Fiction sometimes tries to hard to sound poetic, and the plot is lost. One can read non-fiction with the delicious illusion that the writer didn’t have the intention to show the work to another soul. There’s a feeling of privacy, of directness, and honesty.

Luvvie Ajayi Jones, in her book, Professional Troublemaker, called this the quality of being able to write as if no one were reading. What does it mean to write “like nobody’s reading?” The problem with this advice is that it is easier read than taken.

Jones’s gift is the ability to write with honesty and directness. The prose is often bland, but at least it is real. In ten years, she went from relatively obscure blogger to New York Times bestseller. She explains, “When you are writing like nobody’s reading, it’s going to come out in the truest way possible because there’s no agenda.” But if it were that easy, everyone would be doing it.

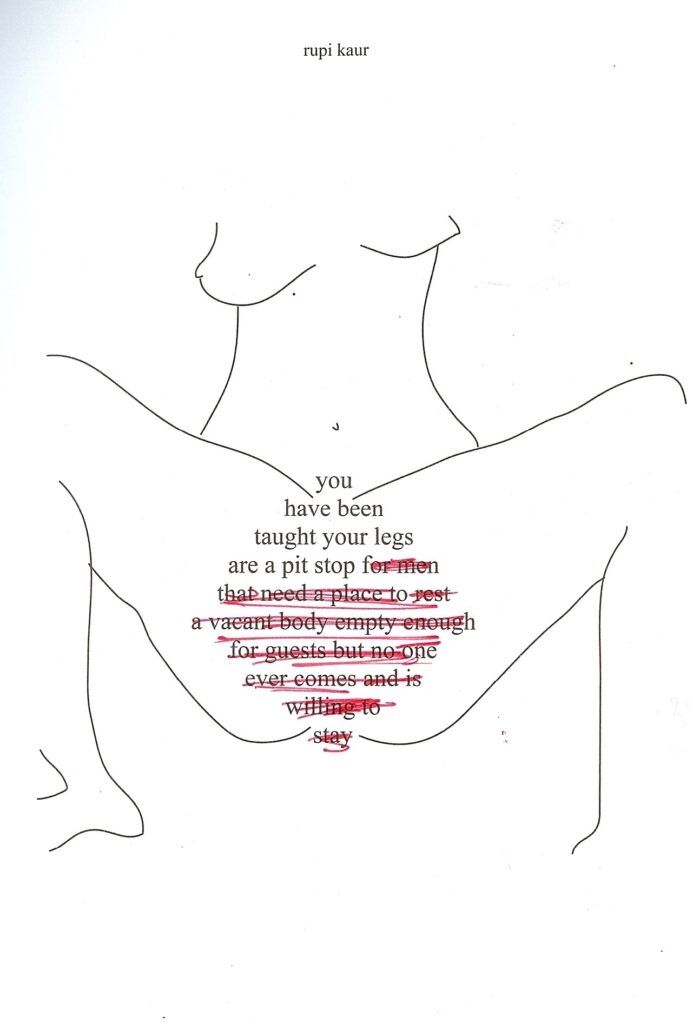

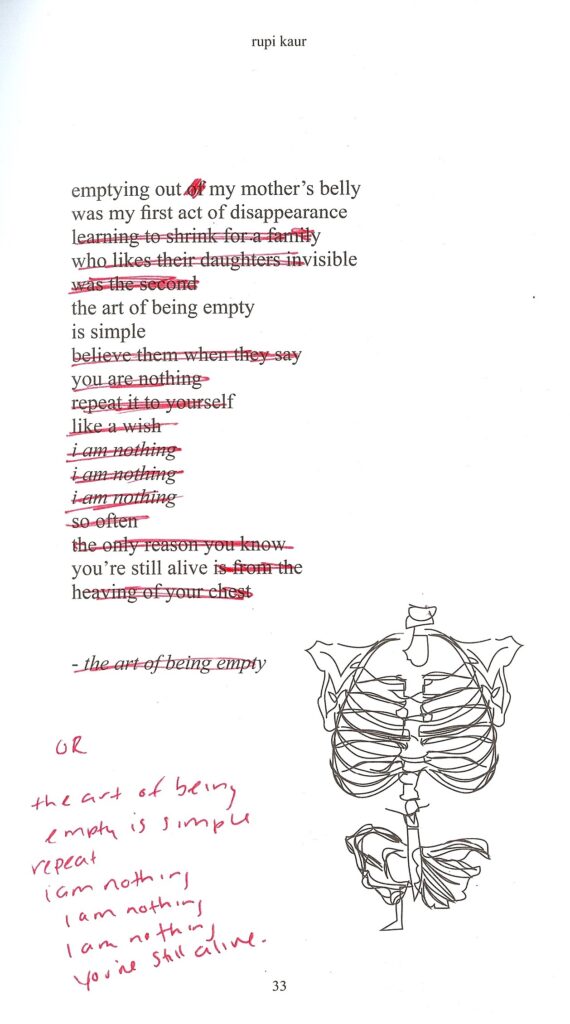

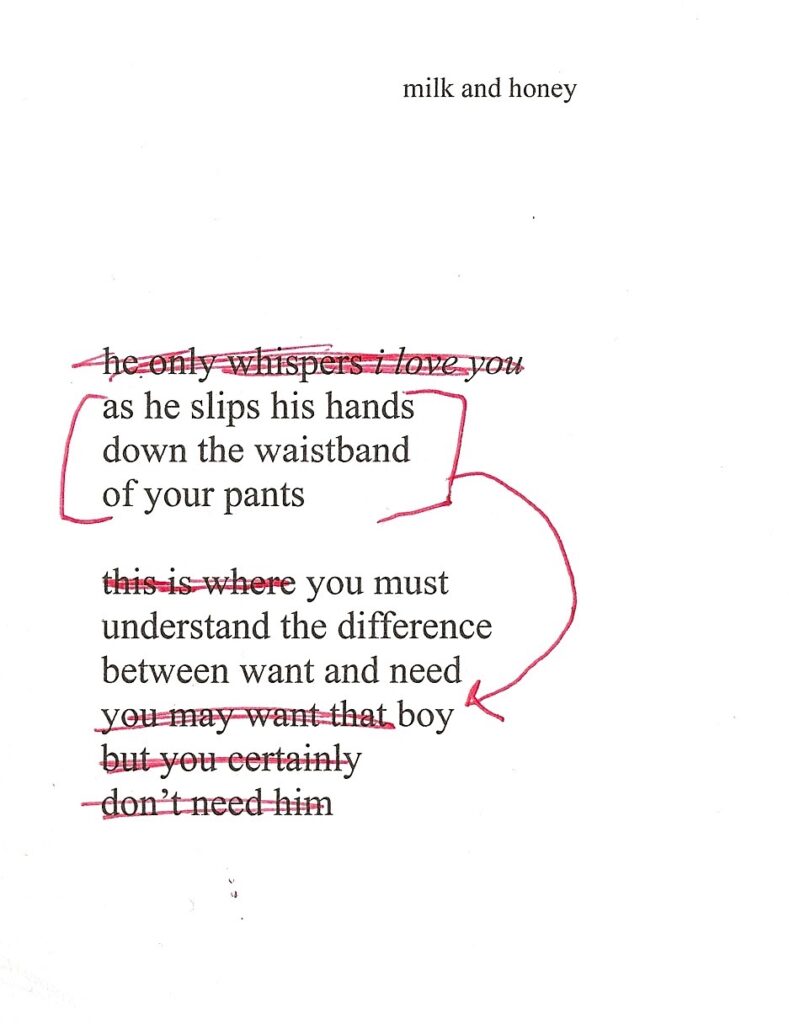

Jones explains that she gained her audience by coming from a place of raw honesty. It sounds easy enough, but raw honesty is very difficult to do. Telling the truth and writing honestly without artifice can be incredibly frightening. It’s far easier to hide behind the veil of your own artifice, simpler to cloak your trauma in allegory, relatively painless to tell something slant. When you put a piece of work out into the world, the public act cannot be easily ignored. It is very difficult to come from a place free of self-consciousness, even in non-fiction.

The self-consciousness of course, comes from the imagined reader. Often this reader takes on the form of the least charitable critic. A good writer keeps this critic always in her head, but hopes never to encounter her in the flesh.

One of my mentors, told me to never read the comments. Young writers in particular need to be especially cautious. If you spend all your time responding to critics, it will be impossible to find your voice and tell your story. But this is not writing as if no one is reading. One can write from a place of self-consciousness and still not read the comments.

The desire to not read the comments comes from an avoidance of meaningless criticism. To keep going, you need to break through the noise. But if you do hear the noise, Jones writes: “…writers don’t stop because people critique them, no matter how harsh they think it is. They don’t abandon their craft because they feel misunderstood or their feelings get hurt. They don’t leave their purpose behind because they have loud detractors. They take the mistakes they made and let them spur them to make even better art.”

It is important to filter the critiques you receive. Are the critiques coming from a random person with no knowledge of what they are talking about, or is the critique coming from an expert? Is the critique coming from someone you love and from a place of love, or is the critique coming from someone trying to elevate themselves by bringing you down? Understanding the difference and responding accordingly can shape or break your art. It can also shape or break a self.

I struggle with “writing like nobody’s reading.” I sometimes wonder whether the work I’m doing is reaching anyone, is helping. After all, why write at all, if it isn’t helping in some way?

But perhaps it doesn’t matter. What if the work is truly for you? Only then, perhaps, could the work take on the quality of authenticity. Then, and only then, might it lose some of its self-consciousness.

I often struggle with the futility of writing this little blog in a world with so much noise. Surely, there are other places to read about literature. There’s the New York Times book review, for one. If it is futile, why keep writing? If you’re doing it right, it doesn’t matter if it is received by anyone else. The work is then truly for you. Perhaps that’s the best work for other people, too.

About the Writer

Janice Greenwood is a writer, surfer, and poet. She holds an M.F.A. in poetry and creative writing from Columbia University.