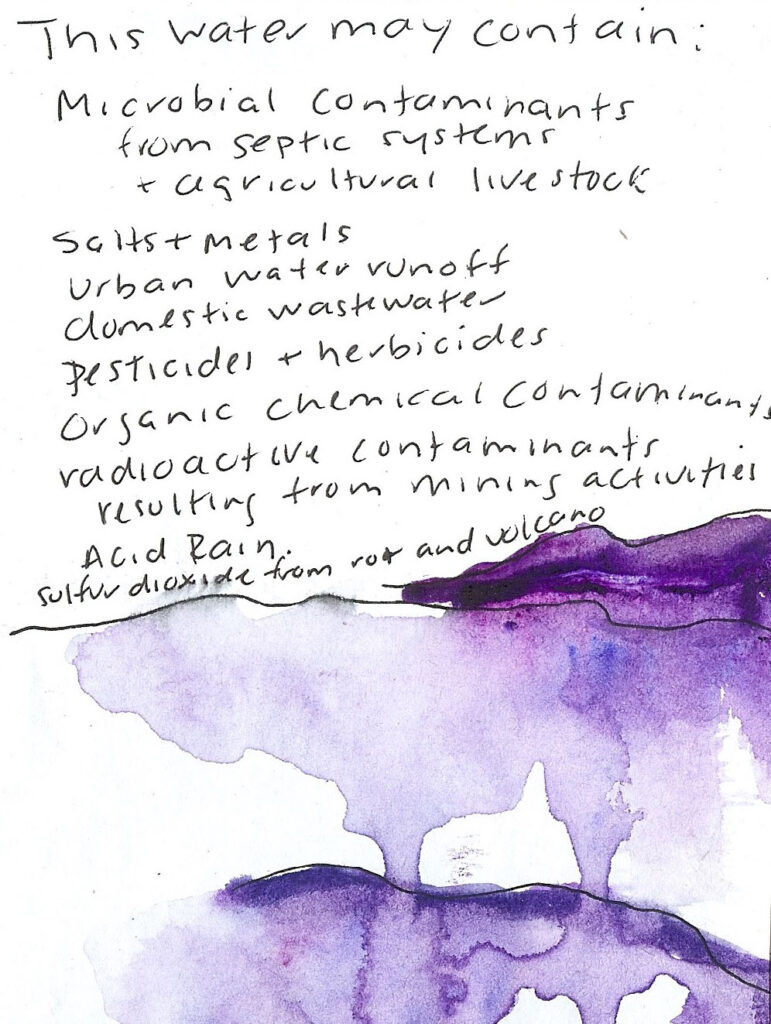

Michel de Montaigne’s essay “On Habit” explores the nature of habit and overwhelm. Contemporary life feels designed to keep us in a state of near-constant overwhelm. I have a pile of books I’d like to read that I could stack literally from the floor to the ceiling. There are birthdays to remember and birthdays I’ve missed, but my love is strong, and I’m trying my best. There are work deadlines. There are projects to complete and emails to answer. There are fans to turn on because today is so damn hot. And then there’s climate change. The Toronto Star reports that Vancouver’s extreme heat is causing mussels, clams, and snails to “cook to death in their shells.” There’s impending drought in California. In Oregon a river runs dry while a fish species sacred to an entire tribe dies en masse, drowned by air. I’d go for a walk on the beach in Waikiki, but at high tide, half the beach is gone. I’d choose solipsistic solutions, but my cell phone is a ticking time bomb of overwhelm. How many inspirational quotes can I read in one hour on Instagram? How many aspirational lifestyles can I imagine trying to lead?

To add insult to the inundation is the fact that there’s a whole library of self-help books out there to overwhelm you with quick fixes to help you feel less overwhelmed. Popular articles offer a range of simple and banal solutions. For example, Inc. magazine lists exercise, deep breathing, gratitude practice, meditation, napping, drinking water, phoning a friend, asking for help, and (this was my favorite) downright procrastination (which can be achieved either by performing deep cleans of one’s desk or by blowing off one’s obligations entirely by going to the movies). I’ve tried all of these recently except going to the movies because every movie seems to be derived from some Marvel comic or another. Do people not write scripts anymore?

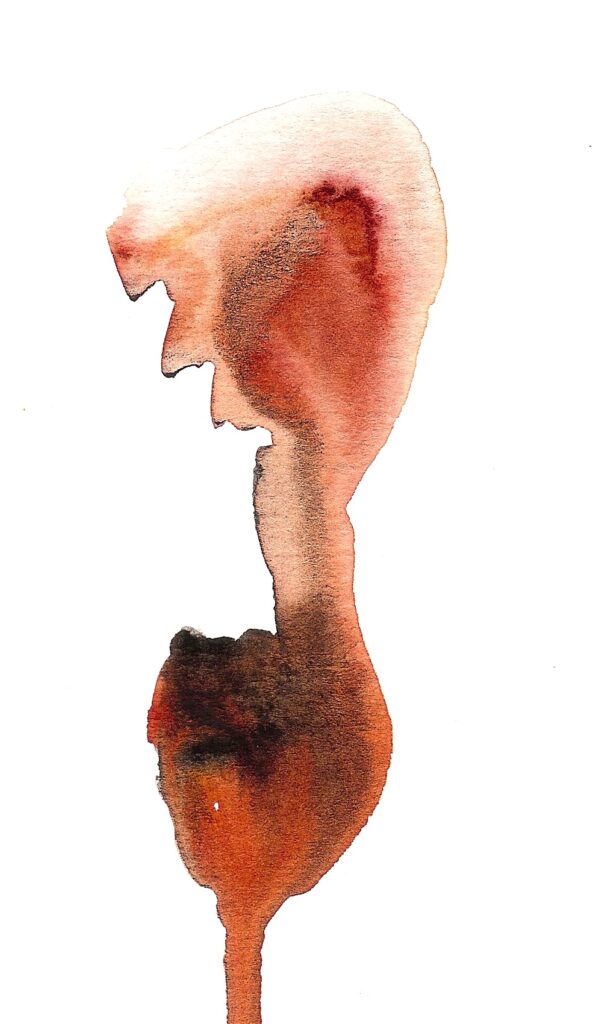

Being a seeker of non-banal solutions, I decided to see what Michel de Montaigne had to offer on the subject. Montaigne, for those who do not know, basically invented the personal essay. So, if you happen to be a teenager or young adult overwhelmed because there is a college essay due, you can blame Montaigne. Given that Montaigne is the cause of so much overwhelm, I thought it appropriate that I’d search within his thousand-plus page tome for a solution. I was not disappointed.

To Montaigne, the solution to overwhelm is habit and the source of the problem is also habit, “a violent and treacherous schoolteacher.” Habit is only as good as the quality and intention of one’s habits and so habit performed without intention leads us down the thorny and wide path to overwhelm. “Gradually and stealthily she slides her authoritative foot into us; then, having by this gentle and humble beginning planted it firmly within us, helped by time she later discloses an angry and tyrannous countenance, against which we are no longer allowed to lift up our eyes.” This should be the first quote presented to every person about to embark on the terrible habit of scrolling through Instagram.

In “On Habit,” Montaigne writes about the king who made it a habit to “draw nourishment from poison” and the woman who grew accustomed to survive by eating spiders. By this he means that we have many strange habits of which we are not aware, and that the human spirit, body, and mind can become habituated to almost anything. Montaigne notes: “Our judgement’s power is lulled to sleep once we grow accustomed to anything.” I live in Hawai’i, where it is all too easy to become habituated to beauty, and so I often stand at the corner of Ka’iulani and Kalakaua just to hear the tourists coo about the houses glowing down the mountains of Manoa like lava flow, like something one would expect to see on the Amalfi Coast.

Either way, there are habits formed in daily life and in childhood of which we may not be aware, that form the foundation of our moral dysregulation, not to mention, mental dysregulation. I’d argue that materialism and excessive consumption is one such habit on which we have all been nursed since we were children (I think of all the weekend trips I took with my mother to the mall). I was also fed Coca-Cola in my baby bottle, which led to a soda and sugar habit. Mere repitition and parental introduction does not make something in itself, right. It might be wise to step back and think about the source of our overwhelm: whether it is to climb the burning ladders of fame, accumulate an increase in social media followers, amass wealth, or accomplish other forms of excess. Sometimes the overwhelm is a symptom of our unequal society, one which glorifies billionaires who construct rockets (blatant vainglorious dick-measuring), while the planet burns, people starve, and millions in America live paycheck to paycheck, in fear of losing their jobs.

And yet, #overwhelmed and you’ll find a swarm of banal solutions and scripts to help you say “no.” Prayer and meditation are often presented as options, but one can neither pray nor meditate on a day where the temperature reaches 116 degrees without fear of heatstroke, nor sit on a beach fouled by the stench of mussels cooking in their own shells, nor swim in an ocean where the jellyfish and corals are literally being boiled alive without risking being boiled alive oneself. And those are the lucky ones. Try taking time to meditate while working two jobs and raising children. Montaigne doesn’t think much of the habit of religion anyway, noting that he will not delve too deeply into the “deceit of religions, which, as we can see, has intoxicated so many great nations and so many learned men.”

Habit can build us up or kill us. Montaigne spends a good portion of his essay “On Habit” listing the many strange habits of cultures and peoples. It’s a thrilling smorgasbord to which I’d add: Americans throw fire in the air, blow up a few children, and terrify their animals on the Fourth of July to celebrate freedom. Montaigne himself wrote: “In the past, when Cretans wished to curse someone, they prayed the gods to make him catch a bad habit.”

Habit can seem ordinary to a culture, or feel almost ordained by nature. Montaigne is such a rigorous thinker as to question the source of all his habits and his culture’s customs.

But Montaigne falls short of calling for outright revolution, even in the face of custom and habit’s absurdity. Here is where I have to disagree. “I abhor novelty,” he writes, saying that “innovators do most harm” particularly those who have so much “self-love and arrogance in judging so highly” of their own “opinions” that they are “obliged to disturb the public peace in order to establish them.” Montaigne was a comfortable man with leisure to read and time to question the very precepts on which his society was based. The billionaires building rockets surely must think the current system a fair one, blasting them to the stars on unpaid tax dollars while children starve, disease rages, drought drains our rivers, and gamblers declare bankruptcy while student loan holders rarely receive such forgiveness. But while the Amazon deliveries always arrive on time, what happens to the Amazon’s actual trees is another story.

Revolution would certainly disturb Montaigne’s comfort (and also the comfort of so many still benefitting from the current arrangement), and so his calls to uphold common laws and to justify those laws on the basis of religion are so loaded with contradictions and bias that they cannot be taken seriously. Wasn’t he just earlier criticizing the folly of religion to provide a justification for all types of stupidity?

He is right to note that the best intentions carry unintended consequences, and we are wise to consider these consequences before we go grab our pitchforks. But, after careful consideration, with the planet burning, it may be time to grab the pitchforks to stoke the flames of change. For those thinking of setting new habits, maybe the first habit should be a rigorous questioning of all current habits.

Perhaps the strongest case Montaigne makes is the case that we each question our own habits, our own fashions, and our own customs, within reason. So many of the habits of overwork and material consumption are the same habits responsible for the planet’s desecration. If we all slowed down a little more, we could do much to assuage the overwhelm and perhaps heal the planet. Perhaps when we are overwhelmed, we would be wise to look first at all the small and large habits of consumption, distraction, and foolishness that got us there in the first place.

About the Writer

Janice Greenwood is a writer, surfer, and poet. She holds an M.F.A. in poetry and creative writing from Columbia University.