Seamus Heaney called Han Shan’s poetry “enviable stuff/ unfussy and believable.” Like everything simple, the surface of the poetry is like a calm sea that belies depth and marvels beneath. Heaney writes: “Cold Mountain is a place that can also mean/ a state of mind. Or different states of mind.” Han Shan’s poetry is about the search for home. Though the poems are about travel, they are ultimately about how a mind at home with itself carries home always with it. When I have felt unmoored, Han Shan’s poetry always feels like a small habitation, a small habit of language I can repeat like an incantation or spell. Recite these poems and you can’t help but feel at home.

Gary Snyder’s beautiful translation of Han Shan’s poetry has accompanied me through various life transitions. The fact that the book remains with me is somewhat remarkable. The book made it with me across the Canadian border when my visa expired. It was one of the books I kept in my tent in Kentucky when I spent a few months camped behind a pizza shop. It survived a tornado that tipped over trucks and trailer homes. I kept it next to my surfboards and climbing gear when I lived out of my van, crossing deserts, searching for cold mountains of my own. I took it with me when I moved across the Pacific, landing in Hawai’i.

Han Shan’s Cold Mountain poems travel well.

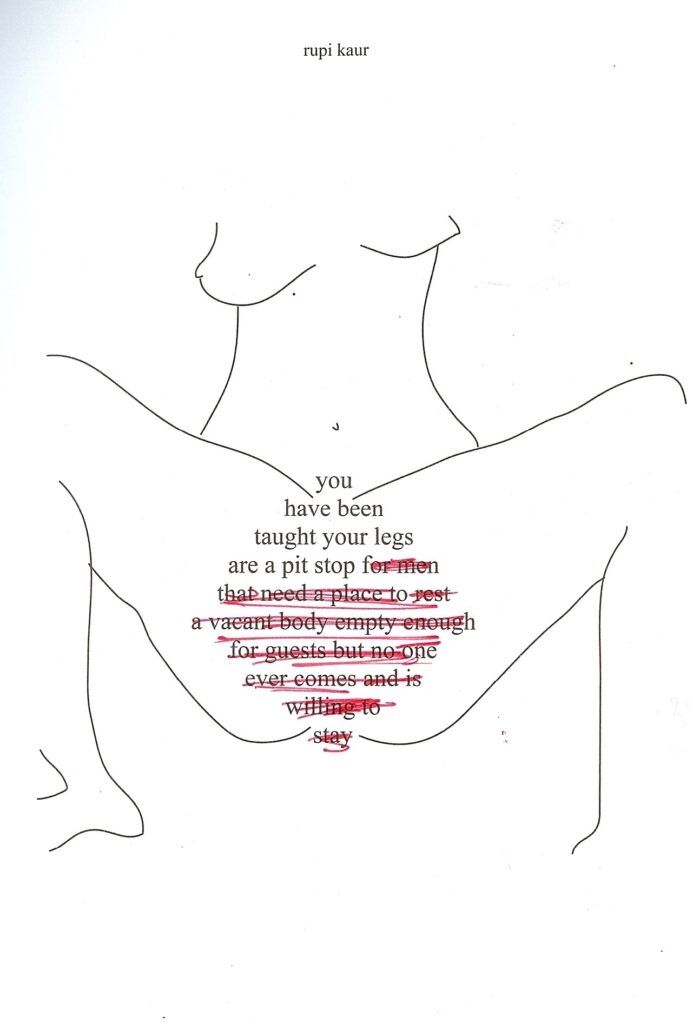

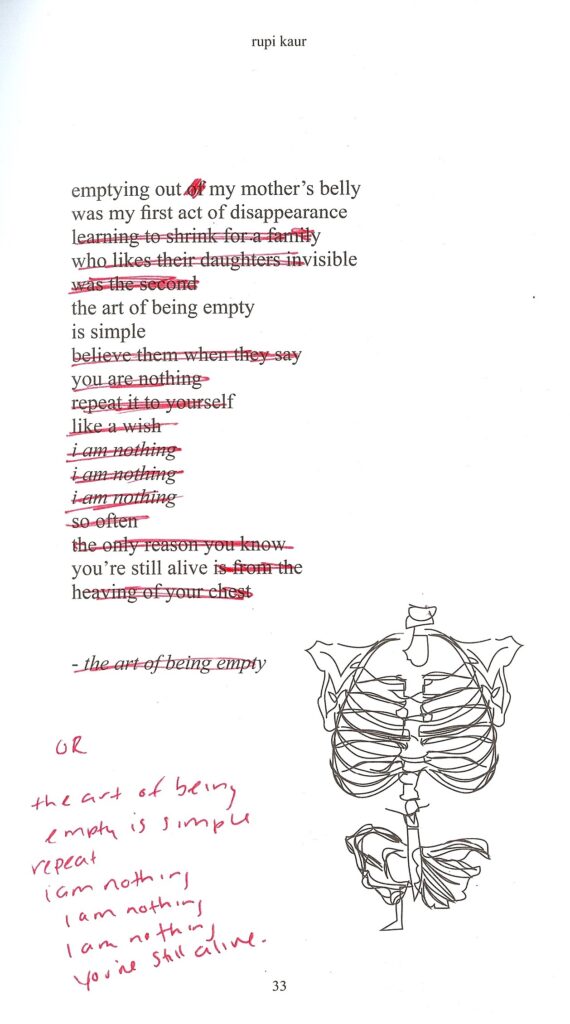

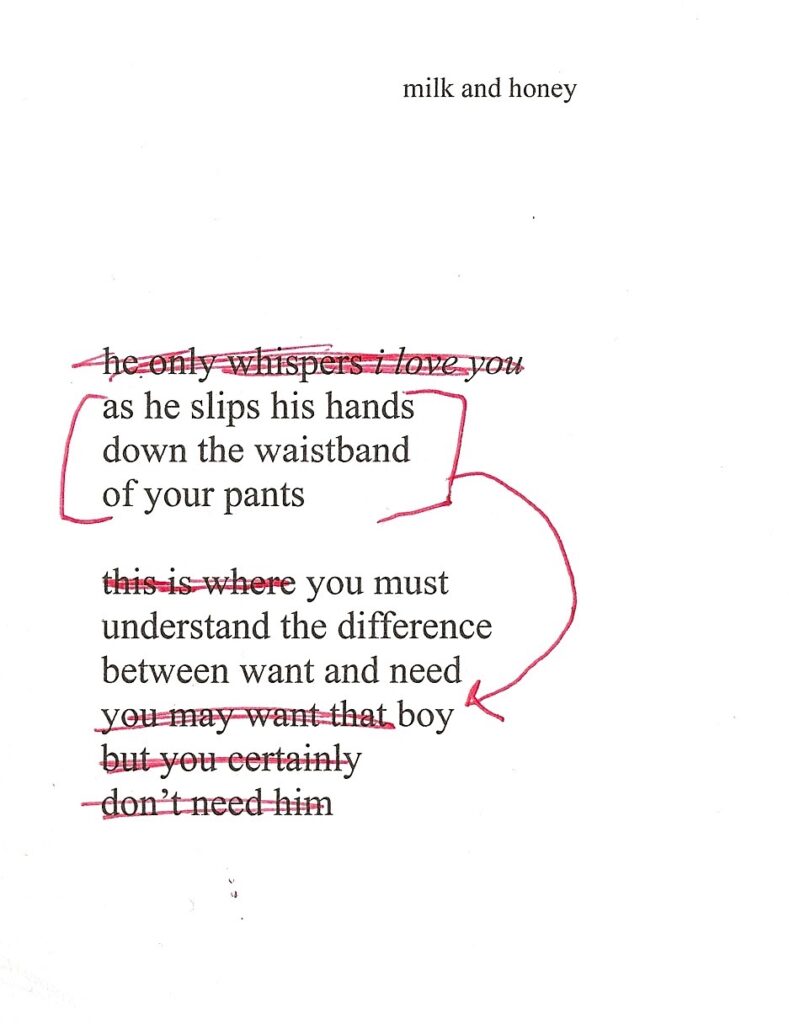

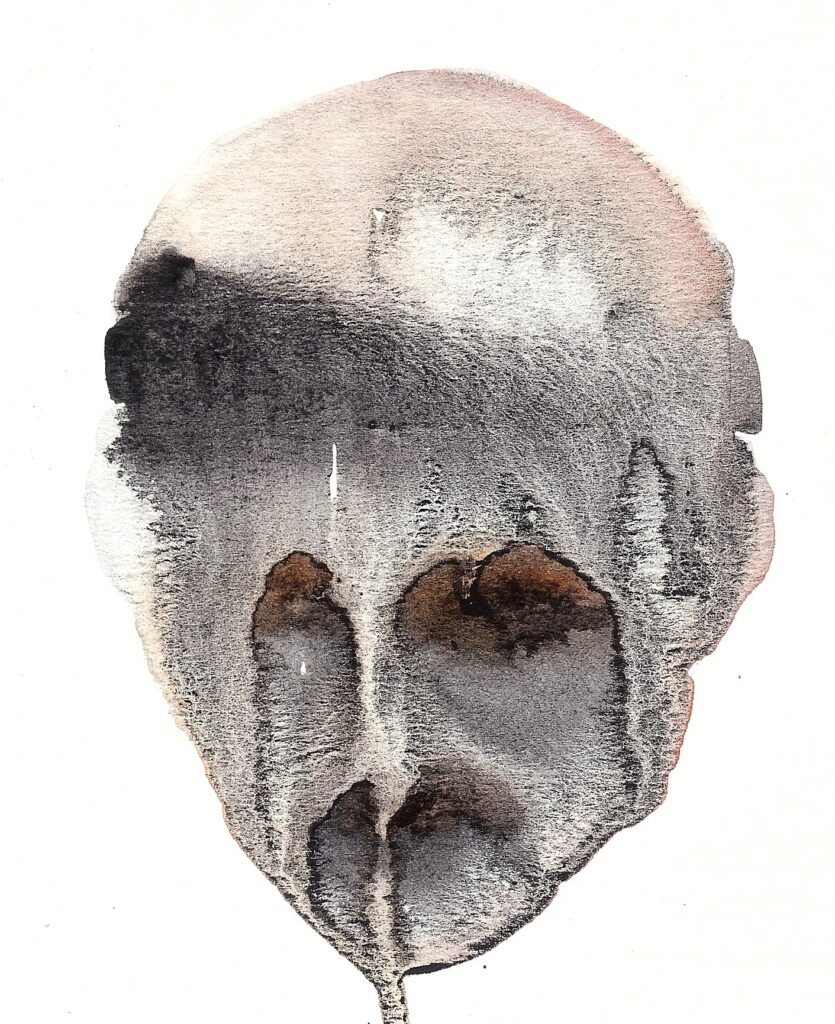

The book elegantly combines the poetry with simple Zen-like drawings of mountains, leaves, insects, and birds. The simplest things are the most difficult to do well, and Gary Snyder’s translation of Han Shan’s Cold Mountain poetry is done well.

In his introduction to the poems, Snyder explains that when Han Shan: “talks about Cold Mountain, he means himself, his home, his state of mind.”

Who was Han Shan? No one really knows. Some say he looked like a tramp. But it is written that he was a wise man, a man who understood the Tao. In the introduction to Snyder’s translations, Lu Chiu-Yin, the governor of the T’ai prefecture notes that Han Shan’s poems were found written on bamboo, wood, stones, and cliffs, and on the “walls of people’s houses.” Like Jean-Michel Basquiat and Banksy, it appears that Han Shan found his start in the ephemeral and undeniable medium of graffiti.

The poems feel like visitations. They have the force of epiphany, the mystery of koan, and the weight of wisdom. They are deceptively simple, invite re-reading, and open with each reading to new interpretations.

Ultimately, though, the poetry is about home, about the long roads we must take to find our home in this world. “The path to Han-Shan’s place is laughable.” The way to Han Shan’s house is found on “bird paths, but no trails for men.” There is a monastic simplicity to the life Han Shan has chosen. “Go tell families with silverware and cars/ ‘What’s the use of all that noise and money?’” Han Shan’s poetics is a poetics for the seekers. It is a poetics that eschews the material realm. The words are spare because they have been reduced down to almost pure spirit. One gets the feeling of looking at Zen art when reading them.

I found Gary Snyder’s translations of Han Shan’s poems when I was myself very much lost in the world, searching for my home in it. I’d recently gone through a separation, which would later become a divorce, which would mean my visa in Canada would expire and I’d have to say goodbye to the home and friends I’d known for five years in Toronto. Where would my home be? It would become a tent in Kentucky, a car in the woods, an apartment in Park Slope, my parents’ house in Miami, and later their apartment in Portland, Oregon. And eventually it would be Hawai’i. Every stop along the way, I have asked: is this home?

“Men ask the way to Cold Mountain/ Cold Mountain: There’s no through trail,” writes Han Shan. How do we get home? We walk, we live, we breathe. The way home, to our true home, often involves solitude, no person can walk the whole path with us.

I’d find myself returning to these lines:

“My heart’s not the same as yours./ If your heart was like mine/ You’d get it and be right here.”

Gary Snyder’s translation is accompanied by strikingly simple illustrations. They are spare. They make room for white space. They breathe, like the poetry.

A great deal of time passes when you are on the path, when you are traveling the way. When you return, everything has changed. I think of my family and friends on the mainland. They were once an airplane flight away. Now, in this world of pandemic and disease, I’m not so sure.

I live on an island.

Han Shan tried many things as a seeker. “In my first thirty years of life/ I roamed hundreds and thousands of miles…Tried drugs, but couldn’t make immortal;/ read books and wrote poems…Today I’m back at Cold Mountain.”

I brought Gary Snyder’s translation of Han Shan’s Cold Mountain poems with me to Hawai’i. Even in Hawai’i, the ocean can sometimes feel cold, especially on days when the waves loom on the horizon like mountains just barely glimpsed. I thought I’d be scared in the ocean swells. Instead I felt calm. Calm, and awe. Sometimes the waves catch you off guard and you get sunk down into the depths of the sea, where there’s no breath, only dark silence. Those moments are the most peaceful. In the ocean, there are times where there’s nothing to do but calmly resign yourself to your fate. The wave will crush you, or it will carry you to shore. Either way, it’s not your choice. There’s a simplicity to being in the ocean. It’s at once a state of meditation and survival.

Cold Mountain poems are poems about the simple life. They’re poems about the simple walk home. When my life gets too complicated (or when I make my life overly complicated) Han Shan’s poetry reminds me that sometimes, all you need to do, is walk, jump in the sea, follow the birds where they go.

For Han Shan, the trappings of society are prisons we build for ourselves: the mortgage, the car, the possessions… “He just sets up a prison for himself./ Once in he can’t get out. Think it over–/ You know it might happen to you.”

The only way out is to live simply, “off mountain plants and berries.” What is there to worry about in this simple place? “Go ahead and let the world change.”

Ultimately, Han Shan taunts and dares his readers to go out and live a bigger life, by which he means—a simpler life. The poems are a message across time and space, delivered to the city and to the lost. “All I can say to those I meet:/ ‘Try and make it to Cold Mountain.’” Can we all make it to Cold Mountain?

All my life I have been trying to get to Cold Mountain, Han Shan. When I’m out in the ocean with the waves, sometimes I feel like I’ve made it at last.

About the Writer

Janice Greenwood is a writer, surfer, and poet. She holds an M.F.A. in poetry and creative writing from Columbia University.