David Foster Wallace has been praised as the “best tennis writer of all time” (the Guardian). But I hold that Wallace is the best sports writer of all time. A few years ago, Library of America released a special edition of David Foster Wallace’s writing on tennis called String Theory: David Foster Wallace on Tennis, and the slim volume captures his tennis writing in one place. But for the purposes of this essay, I want to focus on the piece of tennis writing I consider his masterpiece, the one that for me established Wallace as a nonfiction writer worth reading. This was the piece David Foster Wallace wrote when he reported on the Canadian Open, particularly on the Qualifying Rounds of the Canadian Open, and the struggles of Michael Joyce—a tennis player not quite ranked high enough to compete on the same playing field as Agassi, Sampras, or Becker, but strong enough to almost qualify for the opening day. Joyce was like a AAA baseball player, ever the bridesmaid, never the bride. The essay is called “Tennis Player’s Michael Joyce’s Professional Artistry as a Paradigm of Certain Stuff About Choice, Freedom, Limitation, Joy, Grotesquerie, and Human Completeness.” In the essay, Wallace’s inquiry goes beyond the game of tennis, delving into tougher questions about our society and professional sports in general. He muses on questions of greatness and what that means.

What does it mean to be good enough to occupy the same court as these top professionals, but not quite be good enough to be a household name? This is where Wallace’s writing shines.

I don’t give a crap about tennis and I have maybe watched a total of two hours of professional tennis on television in my life, but I find myself in complete thrall when reading Wallace on the sport. These aren’t essays about tennis, but essays about life, love, sacrifice, hubris, humility, and the limits of human ability and achievement.

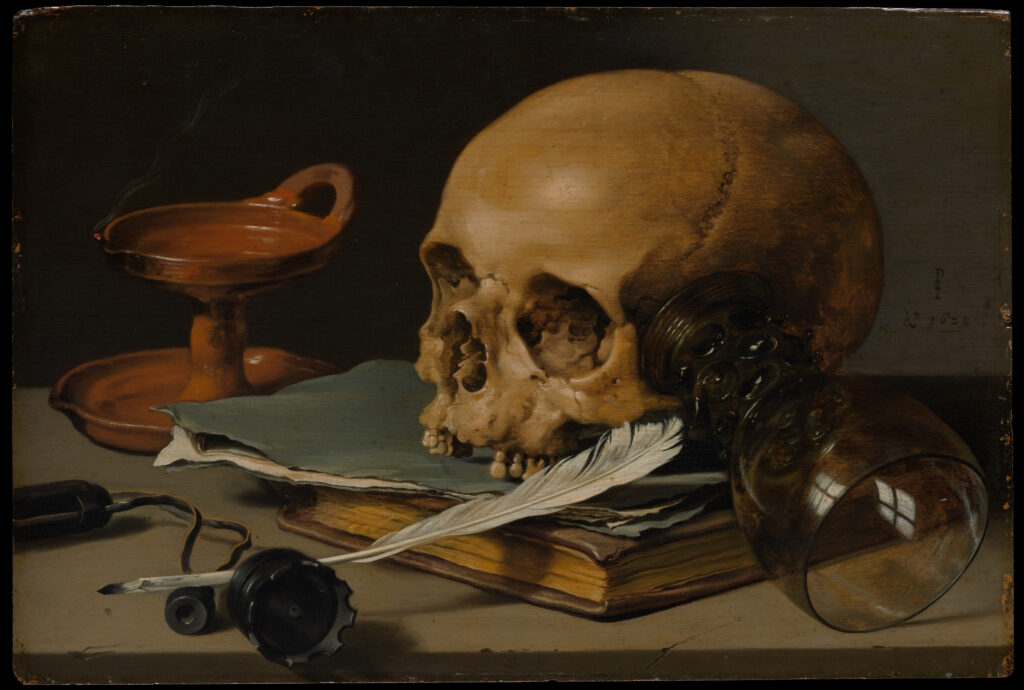

What does it mean to be truly great at something? What does it mean to witness that greatness? What does it mean to compare oneself to greatness? And what are the costs? We are a society that worships at the altar of athletic excellence, but seldom discusses openly the personal and social costs that excellence entails. Because so many of us have seen professional players on television, and few of us have seen them perform up close, many of us don’t even know what that looks like on the player’s level.

Wallace had never seen a professional tennis player play before attending his first live professional tennis tournament in Montreal. Before going to the Canadian Open, Wallace writes about how he had considered himself a fairly good tennis player, a top regional-level player who never qualified for the national tournaments. He imagines that he’ll show up at the Canadian Open and maybe even be able to hit around a few balls with a player like Michael Joyce. Wallace later writes that for him to occupy the same tennis court as Joyce would have been “absurd and in a certain way obscene.”

There are levels of excellence that Wallace hadn’t been able to imagine. This concept is fascinating because it goes one step beyond awe, but takes us into a transcendent space.

“If I’d been just a little bit better, an actual regional champion, I would have qualified for national-level tournaments, and I would have gotten to see that there were fourteen-year-olds in the United States who were playing tennis on a level I knew nothing about.”

And so, when Wallace attends his first live professional tennis tournament in Montreal, he notes in his footnotes: “After the week was over, I truly understood why Charlton Heston looks gray and ravaged on his descent from Sinai: past a certain point: impressiveness is corrosive to the psyche.” In the margins, when I first read the essay years ago, I had added: It’s also why museums are so damn exhausting.

“You are invited to try to imagine what it would be like to be among the hundred best in the world at something. At anything. I have tried to imagine; it’s hard.” This is the line that gets me because Wallace is one of the best in the world at something, just not something quite as measurable as professional tennis. Again, I think most people would agree that Wallace is one of the best, if not the best writer out there on tennis. Surely Wallace had to understand on some level that his writing abilities put him in the top 100, or at least the top 300 in the world for verbal dexterity? Still, I don’t think Wallace is practicing false humility. I think he understands that there are things in this world for which greatness can be readily measured and things in this world for which greatness cannot be easily measured, and Wallace is interested in measurable greatness.

Though Wallace is a great writer, probably one of the best in the 20th century, he understands on a visceral level that he never had to make the kinds of sacrifices a player like Michael Joyce had to make in order to achieve his greatness as a writer. A writer doesn’t need to be writing from the age of two, or begin competing at the age of seven to have a shot at the bestseller’s list. Writers are formed more slowly, and less painfully than all that. We know that the drafts of a book look nothing like the published book, but a writer doesn’t face the pressure of injury, the ticking clock of age, nor the relentless judgement of objective standards that require winning at all odds. You can be a mediocre writer for years and never publish a bestseller, and then one day, something sticks, and you’ve got it. With sports or other measurable arenas of greatness, you always know where you stand in opposition to the competition, and it takes relentless training to improve even slightly.

Wallace writes: “The realities of the men’s professional tennis tour bear about as much resemblance to the lush finals you see on TV as a slaughterhouse does to a well-presented cut of restaurant sirloin.”

In order to earn the right to compete against a Sampras, Joyce must not only compete in more competitions, he must play against opponents for days before he even gets a chance to occupy the same court as a Sampras. Wallace explains: “qualifiers usually get smeared by the top players they face in the early rounds—the qualifier is playing his fourth or fifth match in three days, while the top players usually have had a couple days with their masseur and creative-visualization consultant to get ready for the first round.”

What’s fascinating about Wallace’s essay about Joyce is that Wallace is much like Joyce when it comes to his status as a tennis journalist. Later in his writing career, Wallace will have access to greats like Federer and get the press pass to the U.S. Open. But when Wallace writes this essay about the Canadian Open, we encounter a writer who, like Joyce, hasn’t quite made it to the “big leagues.” Wallace covers the Canadian Open, not the U.S. Open. He covers Joyce, not Agassi. The unspoken commentary Wallace makes is one of access. A great seasoned tennis writer can spend time with Sampras at the U.S. Open. A green writer like Wallace who has never covered professional tennis will get a press pass at the Canadian Open and maybe get some time with a late qualifier like Joyce.

What does it mean to be as good at something as Joyce is good? Is greatness like this even chosen? Wallace explores these ideas: “Can you “choose” something when you are forcefully and enthusiastically immersed in it at an age when the resources and information necessary for choosing are not yet yours? Joyce’s response to this line of inquiry strikes me as both unsatisfactory and marvelous. Because of course the question is unanswerable, at least it’s unanswerable by a person who’s already—as far as he understands it—’chosen.’”

Joyce loves tennis. Wallace goes on to qualify what this love means: “The love is not the love one feels for a job or a lover or any of the loci of intensity that most of us choose to say we love. It’s the sort of love you see in the eyes of really old people who’ve been happily married for an incredibly long time, or in religious people who are so religious they’ve devoted their lives to religious stuff: it’s the sort of love whose measure is what it has cost, what one’s given up to it. Whether there’s “choice” involved is, at a certain point, of no interest… since it’s the very surrender of choice and self that informs the love in the first place.”

The surrender of choice and self. As a society we love to marvel at greatness, but seldom discuss its cost.

There’s the familial cost, the loneliness, the sheer commitment required at the cost of everything else. Wallace explains it beautifully: “The stress and weird loneliness of pro tennis—where everybody’s in the same community, see each other every week, but is constantly on the diasporic move, and is each other’s rival, with enormous amounts of money at stake and life essentially a montage of airports and bland hotels and non-home-cooked food and nagging injuries and staggering long-distance bills, and people’s families at home tending to be wackos, since only wackos will make the financial and temporal sacrifices necessary to let their offspring become good enough at something to turn pro at it.”

The reality is that Joyce, at 22, has sacrificed his childhood, and good portion of his young adulthood to achieve what he has achieved. I think about how in other sports, you hear some version of the same thing. Kassia Meador, the great longboard surfer says she missed her high school prom but got to spend the time somewhere in the Pacific surfing perfect waves. There is always a trade-off, but I hardly think Meador would choose the prom over the waves. I don’t think Joyce would have chosen the normal childhood over tennis.

On Joyce, Wallace writes: “The restrictions on his life have been, in my opinion, grotesque…But the radical compression of his attention and self has allowed him to become a transcendent practitioner of an art—something few of us get to be.”

The essay is more a meditation on what it means to transcendently practice an art or a craft, and how few of us are capable of truly achieving that level of transcendence. I think the more radical question the essay poses is whether any of us even have a choice when it comes to achieving certain levels of excellence and transcendence. Joyce’s achievement is his own, but it was also gifted to him by the circumstances of his life.

My whole life has felt like a balancing act between trying to excel at my writing and at living. Because I have moved between both worlds—sometimes sacrificing everything for my writing, or climbing, or even surfing, and sometimes returning to the real world of work, friendships, love, and life—I don’t think I have necessarily done either quite well. What happens when you are not even a Joyce, but fall short everywhere? Perhaps you’re just an ordinary person, marveling at excellence from a distance.

About the Writer

Janice Greenwood is a writer, surfer, and poet. She holds an M.F.A. in poetry and creative writing from Columbia University.