Jaron Lanier’s “Ten Arguments for Deleting Your Social Media Accounts Right Now” includes, among his ten arguments, the argument that social media is destroying your free will and that quitting social media is the best way you can resist “the insanity of our times.” I don’t really need ten arguments to spend less time on social media. I feel insane enough as it is without the bots feeding me content designed to make me feel more insane. Instagram Gods, if you send me one more post about the “habits that are destroying your mental health,” I promise I’ll delete you right now.

The less I post and the less time I spend there, the happier I am. I haven’t quite brought myself to quit altogether because I do find that social media works more like a thermometer, allowing me to gauge the “temperature” of the culture. Is today politically “hot” or “cold?” Is there finally a new episode of “This is Us” on Hulu that will give me an excuse to sob uncontrollably while eating ice cream? Social media has the answers. But when it comes to trying to find inspiration, true creativity, art, and poetry, social media is the last place I’d look; I don’t look for inspiration on social media, because it doesn’t promote creativity; it kills it.

Lanier makes the argument that social media killed writing and investigative journalism because of the rise of clickbait. “Everyone, including journalists, is forced to play the optimization game…” How many online magazines have devolved into mindless top ten articles that offer neither substance nor novelty?

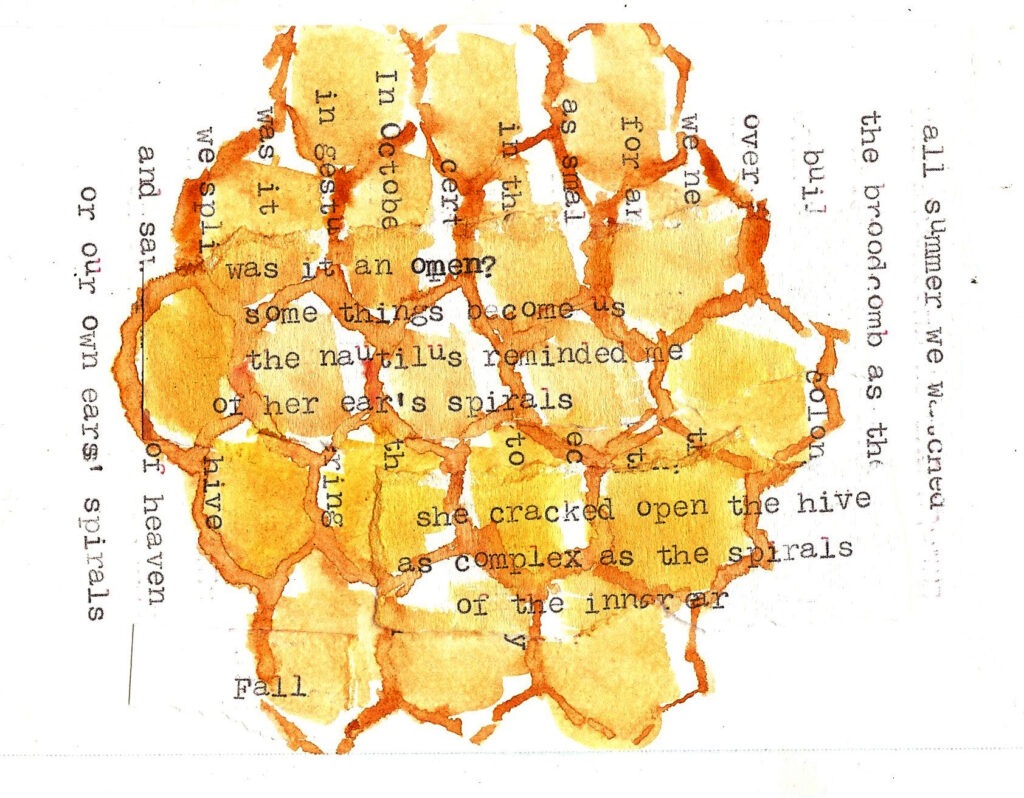

If you look at the art being “liked” on social media, it often involves some combination of naked women (or half-naked women), the macabre, or fantasy creatures presented in various poses. Now, I do know that the history of art was built on naked women, the macabre, and fantasy creatures in various poses (the Sistine Chapel includes all of the above); it’s just that the work on social media somehow lacks an effable quality. I’d refer to this as “soul,” spirit, or what Federico García Lorca called “duende.” It’s one thing to look at a painting of an angel made by someone inspired by trancelike psalms, hymns, and incense, and another thing to look at a picture of an angel made by a person serving the almighty algorithm. The naked women of Instagram are no “Les Demoiselles d’Avignon,” but rather cruder and cruder attempts to appeal to the lowest common denominator—that little heart on the bottom of the screen. There is no memento mori in the macabre of Instagram, only the nihilistic quest for the ever-elusive “like.”

Worse is when artistic creation becomes merely advertisement, the art itself marketing material and product all at once. In Fran Lebowitz’s “Pretend It’s a City,” the great critic and humorist makes the astute observation that when a Picasso goes for sale at the auction houses the crowd is silent. The crowd only applauses once the piece has been sold and the price announced. What are they applauding? The art or the price? I understand that artists need to self-promote and that social media is a great place to promote one’s work. When the self-promotion is self-aware, I can stomach the social media performance. But when the self-promotion becomes an end in itself, I die a little inside, and I think the creative soul dies a little too.

The Instapoet is no better. The poetry ranges from low platitude, to the banal cliché, to the barely silent fart. The most popular poems are as short as limericks, but hardly as profound. What people call poetry on Instagram is often relationship advice or those sad inspirational quotes teachers used to put up on the wall in your math class with pictures of men in speedos diving into a pool, or men with backpacks climbing mountains in silhouette (it was always, always, men). The whole project sounds appealing in concept, but in practice, it leaves one doom scrolling through a hundred posts about how one can better serve the capitalist machine by being more productive, happy, or brave.

Art and poetry deal in more refined neurotransmitters like serotonin and oxytocin, not in dopamine, the elixir of addiction. Social media appeals to the creative quick fix, the feeling of having consumed something profound without any of the labor that often accompanies profound experience. To truly see a Vermeer, one must stand close to it, and then far away. Then, observe the profound subtleties of light, while wondering about the mysteries of the people being depicted, all the while wondering whether it might just be the product of the camera obscura, after all. To see a piece of Instagram art, one need only “like.”

What does it mean to “like” a poem or work of art on Instagram? When critical reception is reduced to such crude binaries, what does this do to taste, to culture? Lanier writes: “Feedback is a good thing, but overemphasizing immediate feedback within an artificially limited online environment leads to ridiculous outcomes.”

Lanier argues that social media is manipulating us and destroying how society works, but it is also destroying art and creativity. When the instant gratification of social media opens the avenues for work to be instantly appraised in seconds by dozens, or hundreds, or thousands of followers and strangers proffering their “likes” or weighty silence, artists are more likely to create work that appeals to the quick appraisal and approval, and fail to create work that requires more pause, more thought. Lanier notes: “What if listening to an inner voice or heeding a passion for ethics or beauty were to lead to more important work in the long-term, even if it measured as less successful in the moment?” The work that often endures isn’t always widely popular right away, but is discovered slowly, and sometimes over a long period of time. And perhaps having the most readers or followers doesn’t always translate into the most value. What if you meaningfully reached only a few people, but actually changed their lives?

On social media, the commodity is the “like.” Likes are virtually free, only taking up our time, but to receive more of them is a strange and empty kind of wealth.

Lanier holds that social media makes people addicted. They become addicted to the dopamine rush of instant approval. Artwork created in this environment, where it is meant to be quickly consumed and dissolved into the forgotten past or at least until the next post, cannot thrive or survive. I make art because I want it to endure, not because I want the pressure cooker of having to post a new piece every day in order to keep my hungry followers happy.

“The addict gradually loses touch with the real world and real people,” writes Lanier.

When I started posting poetry on Instagram, I thought it would serve as a motivation to get me to write. It worked, but I also found myself obsessed with data, watching the demographics of people who chose to “like” my poetry, watching the demographics of those who chose to follow me (young women, mostly; actually young women, only—when it came to my poetry). When I pursued a more robust experiment, where I promoted a poetry post, I learned even more. Young women are the main consumers of online poetry; virtually no men responded to my promotion (was this because the algorithm only showed my work to women? Or because men were genuinely uninterested?). I don’t post much poetry online anymore because I found that the worst poems I wrote were most liked. This instant critical evaluation, I realized, would only have a negative effect on my work.

I’m lucky. I’ve been writing for over a decade. I know when something is bad for me and my writing. But young poets don’t have experience or the understanding to understand that risk-taking work may not be liked, but is the most important work you’ll do because you’ll grow from it. Lanier notes: “When people get a flattering response in exchange for posting something on social media, they get in the habit of posting more.” When young artists confuse a proliferation of likes for the merit of their art, they fail to grow, fail to evolve, and fail to produce challenging work. Pick up any book by an Instapoet and you’ll see what I’m talking about. (Or check out my review of Rupi Kaur’s work, here and here).

What if the best thing for creative life is to create for a while with no one really seeing or judging your work? Lanier writes about this fact about social media as “the inability to carve out a space in which to invent oneself without constant judgement.”

Social media also tends to promote negative emotion, because negative emotion sells. Art and poetry that promotes sympathy, respect, empathy, and compassion is not going to end up in the feed. But art and poetry that feeds on fear, hostility, anxiety, jealousy, repulsion, and ridicule will be promoted. What happens when we consume art stewed in fear and anger alone, rather than embracing the full spectrum of human emotion.

Lanier writes that “if you want to motivate high value and creative outcomes, as opposed to undertaking rote training, then reward and punishment are not the right tools at all.” The easy likes, or the pain of being ignored—this is not what makes creativity or art. Creativity and art dwells in community, but it also dwells in a space where there isn’t always instantaneous feedback.

There is nothing on social media that fosters “joy, intellectual challenge, individuality, curiosity” or other elements of the human experience that can’t fit into the algorithm. When we turn art making into an experiment led by B.F. Skinner, we’re all more likely to become more like Pavlovian dogs, drooling at bells, rather than searching for meaning, and deeper truths. Deeper truths are hard, the pithy quote in your feed is easy.

Taking time away from social media, gives one the space to make real art. It gives one time to search for art and experiences that foster art as well. This is something to think about, when you’re not checking your phone to see how many people liked your skull painting or breakup couplet. (Guilty and guilty.)

About the Writer

Janice Greenwood is a writer, surfer, and poet. She holds an M.F.A. in poetry and creative writing from Columbia University.