Emotional labor is defined as the additional work a person performs when he or she is forced to hide feelings in order to maintain a status quo. Originally, the term was meant to be applied to workplace settings, where the status quo was the professionalism of the workplace. The term has since been expanded to include the ways in which emotional labor protects various kinds of status quo–from gender inequality to racism.

The Atlantic reports that the term was first coined by the sociologist Arlie Hochschild in her book called The Managed Heart. Hochschild examines the work individuals needed to perform when managing their emotions in certain jobs. David Foster Wallace would later refer to this phenomenon as “the professional smile.” During the #metoo movement, feminists examined the toll that emotional labor took on women (who are often forced to manage their emotions in personal as well as professional settings). But emotional labor is not limited to professional settings or to gender dynamics. I think now is an apt time to revisit Claudia Rankine’s Citizen, and to take a look at the way in which Rankine’s poetics reveals the ways in which black emotional labor affects the mind and the body.

As I read Claudia Rankine’s Citizen, I found myself encountering so many moments where Rankine had to make a decision: should she call out a racist remark or action, or should she remain quiet–let it slide. Rankine’s book is a reminder of the burden that black Americans have borne in the face of subtle and not-so-subtle racism. In the words of Michael Eric Dyson in his introduction to Robin Diangelo’s White Fragility, “For much of American history, race has been black culture’s issue; racism, a black person’s burden.” The brilliance of Rankine’s hybrid poetry, prose-poem, essay, and meditation on race is the ways in which it subtlety shifts the burden upon the white reader to hold herself accountable for her participation in white supremacy, and to understand the ways in which the burden of race has been placed upon black Americans’ shoulders. Those who are black so often bear the burden of holding racism to account. It is this exhausting emotional labor that Rankine explores in Citizen.

There were two kinds of moments Rankine describes in Citizen. One moment was one in which the white person acting in a racist manner did not realize he or she was being racist. The other moment was the one in which the white person caught their mistake, but refused to openly acknowledge it or apologize for it, thus placing the burden upon the speaker to address the racist remark.

Rankine describes the latter: “Certain moments send adrenaline to the heart, dry out the tongue, and clog the lungs…After it happened I was at a loss for words. Haven’t you said this yourself? Haven’t you said this to a close friend who early in your friendship, when distracted, would call you by the name of her black housekeeper… Eventually she stopped doing this, though she never acknowledged her slippage. And you never called her on it (why not?) and yet, you don’t forget.” There’s emotional labor involved in calling out this kind of racist slip. And the obligation to acknowledge it should fall upon the person who did the wrong.

Rankine describes the disassociation this creates: “You are in the dark, in the car, watching the black-tarred street being swallowed by speed; he tells you his dean is making him hire a person of color when there are so many great writers out there. You think this is maybe an experiment and you are being tested or retroactively insulted or you have done something that communicates this is an okay conversation to be having.”

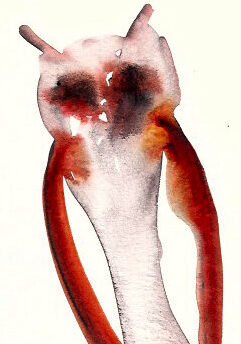

A study published in the journal Social Science & Medicine found links between racism and negative health outcomes. Those in the study who experienced racism were more likely to smoke, engage in hazardous drinking, experience poorer cardiovascular health, poorer mental health, and psychological distress. Another study published in 2015 in the American Journal of Public Health surveyed Black New York City residents who lived in Black New York City neighborhoods. The survey asked respondents questions about instances of racism. Those who experienced racism were more likely to experience “poor mental health days” and those who denied thinking about race experienced the worse effects. The denial of racism, namely, the silence surrounding it, has the greatest physiological and psychological impact. It is this impact that Rankine deftly addresses head on when she describes the “adrenaline to the heart” the dried “tongue” the clogged “lungs.” Rankine’s description of the physiological experience of racism is like a punch to the gut. She explains it eloquently: “the body has memory. The physical carnage hauls more than its weight.”

The reasonable response to all of this is trauma. But when the speaker in Citizen shows up for her appointment with the trauma therapist, “the woman standing there yells, at the top of her lungs, Get away from my house!” And then there’s the moment of recognition, when the speaker tells the therapist she has an appointment, when the therapist realizes that the black person at her door is her patient, not a trespasser.

And then there’s that beautiful essay in the middle of the book about tennis that puts David Foster Wallace’s essays about tennis, Roger Federer, and free will to shame, because all I can see now is Serena Williams’s incredible self-control (does she have freedom to act or respond dynamically and authentically within a system where her every response will be judged through racist eyes, where her every choice is circumscribed by the color of her skin, where her very job is contingent upon her ability to perform black emotional labor and maintain a professional smile?) in the face of racist commentators and racist referees and racist opponents and that image of Dane Caroline Wozniacki with the stuffed bra and panties…

Later, in her “World Cup” “Script for Situation video created in collaboration with John Lucas, Rankine will write: “No one is free.”

And then there’s the “Script for Situation video comprised of quotes collected from CNN, created in collaboration with John Lucas” about Hurricane Katrina, and I can only ask you to read it because I can’t fully put into words the awfulness of it all, and the awfulness of “it’s awful, she said, to go back home to find your own dead child. It’s really sad. / And so many of the people in the arena here, you know, she said, were underprivileged anyway, so this is working very well for them.” And yet. And yet. “the fiction of the facts assumes randomness and indeterminacy.”

And the “Script for Situation video created in collaboration with John Lucas where “The pickup truck is human in this predictable way,” because the pickup truck represents the white man, who murdered James Craig Anderson in a hate crime. Rankine interrogates the ways in which language forgives the white murderer while shifting the burden upon the murdered.

But the brute fact is repeated, as if it needs to be repeated, and isn’t that the point–the fact that it needs to be repeated–how many times does it need to be said that “James Craig Anderson is dead.”

And the “Script for Situation video created in collaboration with John Lucas” on Stop-and-Frisk, where Rankine writes: “You can’t drive yourself sane” after being pulled over because “you fit the description because there is only one guy who is always the guy fitting the description.” And the repetition of the line, the recursion itself is mimetic of the experience because “you fit the description because there is only one guy who is always the guy fitting the description.”

Kate Kellaway, writing for the Guardian notes: “And there is nothing slight about the slights described here.”

What is the antidote to racism? “How to care for the injured body,/ the kind of body that can’t hold/ the content it is living?”

In Citizen, Rankine calls for an open acknowledgement of it– a calling to account. The emotional labor can no longer be put upon those who are Black.

About the Writer

Janice Greenwood is a writer, surfer, and poet. She holds an M.F.A. in poetry and creative writing from Columbia University.