I didn’t expect to actually find any good advice in Rachel Hollis’s new book, Didn’t See That Coming: Putting Your Life Back Together When Your World Falls Apart, especially after Hollis admits in her introduction that most of her book about resilience was written before she actually had to put her resilience advice to the test. Hollis opens her prologue with the following sentence: “Three days into editing this book, my marriage ended.” I expected the divorce to figure more heavily into the book, but the prologue is an afterthought. The book is less about divorce than about the little habits and modes of thought Hollis has used to help her get through the dark times.

I don’t know much about Hollis (or rather, I didn’t know much about Hollis before reading this book)—the brand and the personality—other than that she maintains an incredibly popular blog, has a ton of followers, and has written a bestselling book called “Girl Wash Your Face,” which I haven’t read but plan to read if I ever finally get around to having enough time to actually wash my face. My mental image of Hollis largely comes from a profile of her written by Allie Jones for the New York Times. From the profile, Hollis is portrayed as a mommy-blogger extraordinaire. If the profile is correct, Hollis does more shit by noon than I get done all week—if I’m lucky. In the profile, we are informed that Hollis “works out, feeds her four children… and writes in her gratitude journal” all before airing her daily morning podcast, working on her highly successful blog, and planning her “personal growth conferences.” She also has staff and a team of nannies, which probably helps.

In Didn’t See That Coming: Putting Your Life Back Together When Your World Falls Apart Hollis explains that she lives by a plan. She is a person who has “imagined in detail the next two decades” of her life. I was skeptical. Anyone who thinks they can imagine in detail the next two decades of their life is either a teenager who hasn’t had anything real happen to them or someone who has lived in a bubble of pure unchecked privilege. I immediately created a mental image of Hollis as another one of those stay-at-home-mom-turned-mommy-blogger types; another housewife who burned the lasagna one too many times and decided to write about it.

I was wrong; I was right.

It turns out Hollis has experienced incredible tragedy—you just wouldn’t know it from looking at her carefully curated Instagram feed. The best writing in the whole book comes in the last chapter. It literally took my breath away. When Hollis was a freshman in high school she found her brother’s body after he had committed suicide. She writes about the 911 call, and the aftermath that left her family broken, left her parents emotionally absent. Hollis writes about the process of rebuilding her life afterward.

In a world where social media privileges the glossy view of things, Hollis encourages her readers to confront their pain. And while none of the advice in I Didn’t See That Coming is novel, when you’re in the middle of a shit storm, sometimes wisdom bears repeating.

The feminist heart of the book is the call to own your truth—whatever it is. Hollis writes: “…the grief and the pain that come from staying put in order to keep those around you comfortable are not an indication of a life well lived.” She encourages her readers to ask themselves: “What are the areas in your life where you’ve dissolved boundaries to be present for others at the loss of yourself?” She urges her readers to speak their truth daily, to create boundaries, and to acknowledge that their identities will change over time.

Hollis provides words of wisdom from her therapist: “whenever someone in my life consistently did something that upset me but I didn’t comment on it because I thought I was being selfish to admit that it was hurting me, that was where I needed a boundary.”

Readers who will pick up Hollis’s book are probably more likely than others to be in a lot of pain. Who else picks up a book with “When Your World Falls Apart” in the title? While, the book tries to be too many things at once—there’s a chapter on perspective, a chapter on mindset, and a chapter on managing your finances, there’s a wisdom to throwing everything and the kitchen sink at your troubles. Rock bottom isn’t a time to be picky about your resources. If you think of Hollis as taking the best self-help advice books, distilling their wisdom, and presenting it in her distinctive voice, this is basically what you’re getting. You’d probably get more from reading her sources (which she does often credit), but that would take far longer and, for many, probably be less relatable and feasible.

The simple and obvious advice to take things one day at a time is at once the most difficult and easiest to follow. And when one day at a time seems to be too much, she tells her readers to “focus on the next hour and how to care for yourself for those sixty minutes inside of it.” I wish I could create a digital alert on my phone that could text me those exact words whenever I’ve been triggered or overwhelmed.

Hollis has created a lifestyle brand out of her lifestyle. In a world of Instagram-ready lives, polished for the envy of the masses, Hollis sells a lifestyle more polished than yours, more put together, more beautiful, more fun, more inspiring. She is the ideal for the women trying to raise three kids, have a career, and maintain a happy “traditional” marriage while also occasionally drinking a margarita.

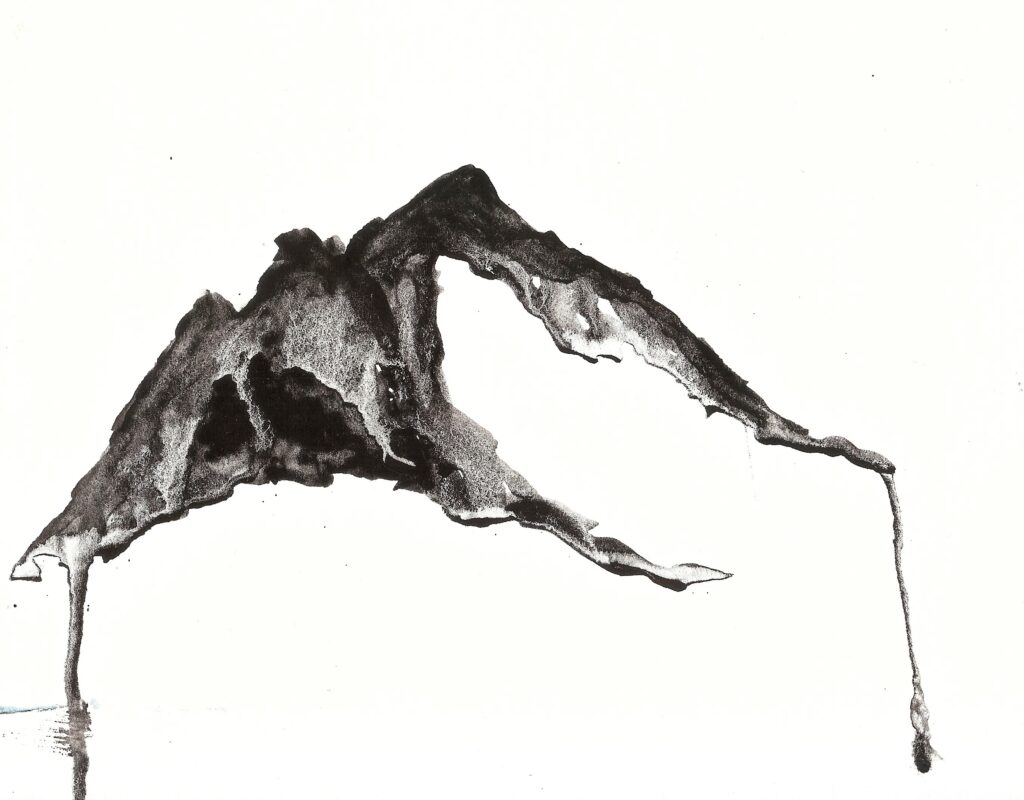

I could sit here and judge her feed, but I fall prey to these illusions myself. We all do. Maybe I’m not trying to be the perfect homemaker and female business professional extraordinaire, but I often find myself looking at pictures of women surfing big waves, climbing wild mountains, or I read the accomplishments of women writers I admire, and the wanderlust hits me; I find myself falling short. Instagram offers a curated feed for every last one of us. I don’t want Hollis’s life, but I also understand that she has harnessed the power of the medium to connect with her audience.

And connection is the focus of Didn’t See That Coming. Hollis advocates for connection with oneself and connection with others.

“If you want to move forward, be honest about what’s going on even if it’s only to yourself.” Admitting the problem is the first step in solving the problem, but I worry that in our culture of curated selves on social media, admitting the problem to oneself is only half the battle. Authenticity, openness, honesty, and connection with others from a place of vulnerability are just as important. In a world that increasingly encourages each person to be their own lifestyle brand, authenticity increasingly becomes the rarity.

Hollis posits that grief and loss are ultimately just identity crises. I tend to stand with Buddha and Shakespeare in believing that identity is performative and illusory and merely the surface social gloss. But Hollis resides deeply in the glossy veneer. To Hollis, grief, loss, and pain come from four main issues: (1) an identity a person had was taken away (you’re no longer a wife because you got divorced; you’re no longer a CEO because you lost your job), (2) you can’t get an identity you want (I can’t get pregnant, so I’ll never be a mom); (3) you don’t want the identity you have (I don’t want to be married anymore); (4) or someone else put you in a role you don’t want (you’re told by someone you love you’re something you know you’re not; this can be the most painful). Hollis’s solution is that we get to choose our identity, reinvent it, and can continue to have whatever identity we want. The solution sounds too flippant, too easy. Tell that advice to the former felon who still can’t vote in this election, the immigrant children still separated from their families, and the men and women killed at the hands of police. Do they get to choose the identities foisted upon them? Choosing your identity is a privilege, and it’s an illusion straight white men and women will most often claim.

Hollis writes: “I truly believe it’s possible to achieve anything you want, with hard work, but you don’t get to control the variables that will make it so or the time frame in which is appears.” But in the wake of the national awakening that has followed the murder of George Floyd and the gut-wrenching reckoning our nation has had to face about institutional racism, Hollis’s words come across as tone-deaf.

I think the source of Hollis’s confusion lies in the conflation of identity and perspective-making. Identity is socially constructed and therefore is collectively constructed. Perspective, however, is chosen. Hollis notes: “your perspective on any and every given subject isn’t necessarily based on the truth, but instead is based almost entirely on your past experiences and what they’ve taught you to think about the subject up for review…you are in control of your perspective.”

Yes, hard work can get us far, but I think this fails to take into account the concept of reality and the reality that outside forces shape us, the reality that we aren’t in control of every outcome. To claim that we have complete control over our identities puts us once again in the digital Instagram-worthy realm of anything is possible with an airbrush, rather than in the flesh and bone, tooth and claw world of institutional racism, structural bias, and Donald Trump.

That said, Hollis’s no-excuses approach to perspective-building is only fair in a world that isn’t fair. And I do agree that the perspective we choose to take can shape our lives. I didn’t have the advantages my trust-funded (and more economically-stable) peers had. My parents didn’t pay for my education, I worked through college, I’m still sitting on an Olympus of student loan debt, my mom is a mentally-ill first-generation immigrant, my dad a traumatized Vietnam Vet, I’m not good at making connections and therefore never really got an editor to champion my work, I’m Hispanic, I’m white, I was born poor, but got a world-class education; I spent half a decade angry and lost, and that got me nowhere. Shit gets done when you get to work, despite whatever disadvantages (and advantages) you’ve been dealt. Shit got done when I changed my perspective and got to work, and understood that my success and failure was a factor of both my hard work and the obstacles and benefits I’d been dealt. By differentiating between perspective (what I could change) and the hand I’d been dealt (what I couldn’t change), I could better gauge my own success and failure when I compared my progress to others.

You wouldn’t know that Hollis is going through a divorce by looking at her social media account, though there is one photo of Hollis on her Instagram account where she has taken a selfie of herself and there is deep sadness in her eyes, the kind of sadness I recognized in pictures of myself in the weeks and months after my own divorce. In between the model-perfect hair, the perfectly styled “Good Housekeeping” type imagery, there’s a moment of honesty that is highly relatable. Her gems of wisdom for navigating tragedy are often buried in the rough of her memoir-style prose. I only wished she’d polished them, shaped them, and set them apart for the jewels they are. I wish she couched her book within the larger narrative of her life. What exactly happened to get her where she is. The specificity of her success and her grief was far more interesting than the generalities and self-help truisms.

As a writer I who creates legal content writing for divorce lawyers, I understand that Hollis’s choice to avoid discussion of her divorce on social media is not very shocking. Most divorce lawyers will warn you about posting anything about your marriage or divorce on social media while going through a divorce.

I think that a true reckoning with grief comes from the ego-crushing humbling process whereby the ego and identity gets completely annihilated. We get divorced, we suffer catastrophic injury, we lose everything. And in that obliterated place, where the ego is turned to cinders and everything we thought we were is drawn into question, we can finally look at ourselves as we truly are, look at our pure essence of love and pain and hurt and hope directly, and build more authentic lives, not structured on false foundations, but built from the unseen connections that bind us together. Identity keeps us separate. All life on this planet is woven together with love and dependency and yes, pain.

About the Writer

Janice Greenwood is a writer, surfer, and poet. She holds an M.F.A. in poetry and creative writing from Columbia University.