Still life paintings which flourished in Holland in the 17th century are visual poems, with a visual symbolism dedicated to depicting the transience of life and the relentless march of time. Images of delight were often juxtaposed beside macabre imagery which included skulls, half-burnt out candles, and sometimes literal animal carcasses. Since then, various artists have taken on the form. Take for instance Edouard Manet’s stunning “Fish (Still Life).”

The viewer is at once confronted with the imagery of both death and desire. The fish would be grotesque and corpselike were it not for the inviting lemon bringing the promise of a coming feast. The creatures retain their form as carcasses, even as the coming meal is alluded to by the opened oysters. The bare white tablecloth evokes the blank canvas, the raw canvas in process, which is synchronous with the subject matter–a meal in the process of becoming a meal. The raw materials are laid bare before us. Manet exposes his bold brushstrokes, thus exposing his process as well.

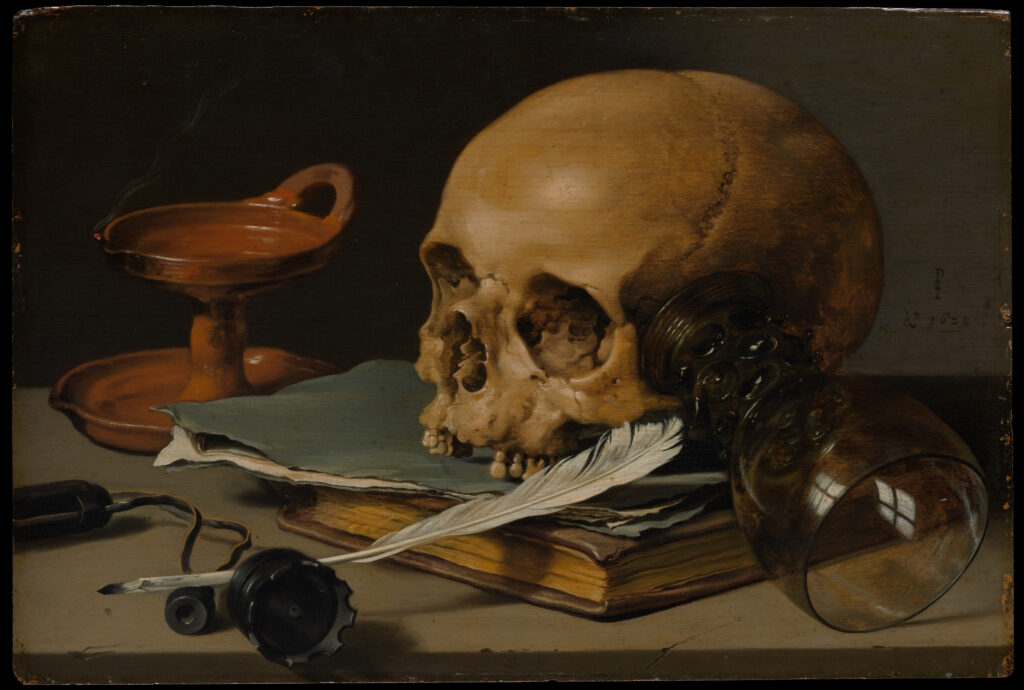

There’s something about all still life art that evokes the process of its creation. After all, to take something unmoving and render it still is itself a commentary on the passage of time. One of the still life paintings I have found myself returning to again and again is Pieter Claesz’s “Still Life with a Writing Quill,” particularly because it evokes writing, which is an act rooted in time, also made timeless by virtue of the fact that it is an art form, like visual art, that can be recorded.

I have been thinking quite a bit about the secular context in which the vanitas still life was meant to reside. Unlike art of the church, which often depicted overt religious symbology, the vanitas was meant for the home (or perhaps, office). The domesticity of this imagery is disrupted by the evocation of death, lending a spiritual essence to objects that would otherwise be quite mundane.

In our era of climate change and mass extinction, we live on a planet that is changing, fragile, and transient. Scenes of nature that would once have had the essence of permanence and unchangeability about them (19th century paintings of glaciers come to mind), now seem transient and fragile. For something to move glacially once referred to a process that was so slow as to be invisible. Now, glacial change is hardly glacial. Forest landscapes, coral reefs, coastlines all feel like drafts of a possible world, drafts of a possible world in the process of erasure, a world erased I hope I don’t ever have to know.

Is our natural world going the way of cut flowers, candles, and cheese, in the Dutch still lifes of old?

About the Writer

Janice Greenwood is a writer, surfer, and poet. She holds an M.F.A. in poetry and creative writing from Columbia University.