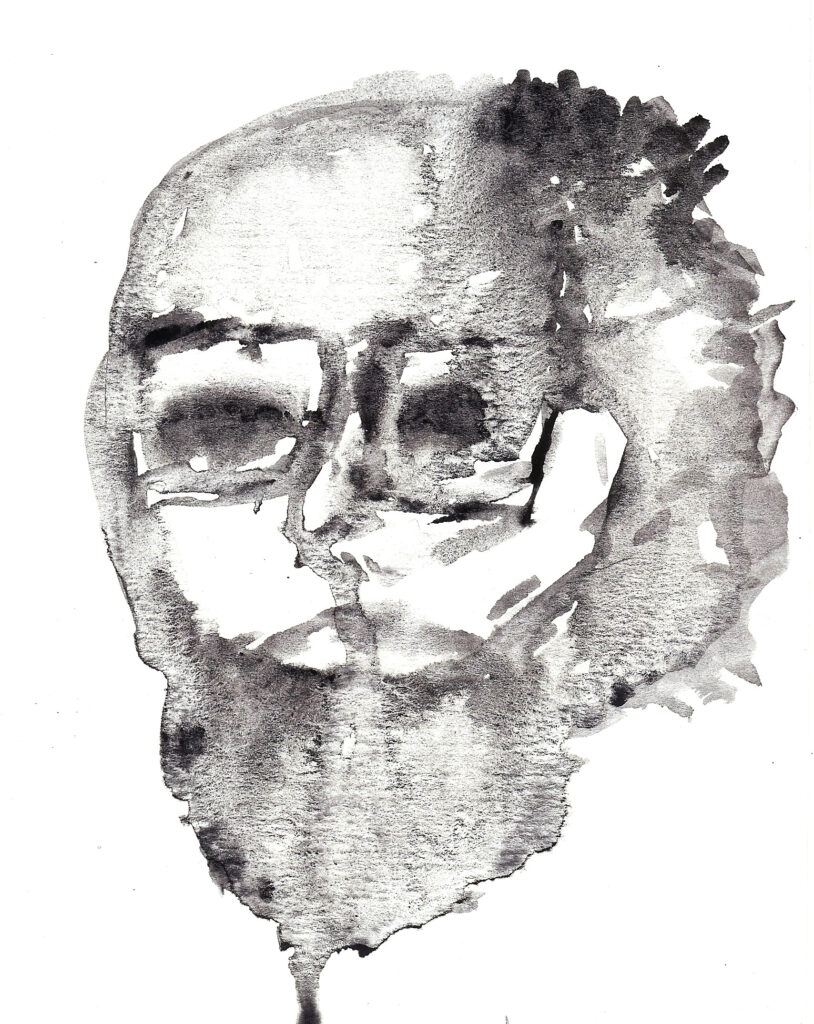

Lawrence Ferlinghetti, beat poet and author of A Coney Island of the Mind, passed away on Monday in San Francisco. He was 101 years old. Ferlinghetti holds a special place in my poet’s heart.

When I was 19 or 20, I had spent a whole summer working as a J.C. Penney lingerie girl (my very unglamorous job involved managing the cashier, putting bras and underwear on hangers, and directing the mostly-elderly clientele who visited our store to the more experienced lingerie girl who had been trained to measure bust size; I also had an affair with a very attractive man who drove a silver Mustang and worked in the juniors department; the plus-size dressing room and juniors room shared a hallway, and we had a lot of time to talk on Sundays when people trashed the place). But I digress. After spending the whole summer swimming in underwear and after the affair with the guy from juniors ended, I decided to take a flight to New York City. I would go there and see great art and read great writers. I would take Lawrence Ferlinghetti’s Coney Island of the Mind with me on the train to Babylon and I would travel to the edge of the manufactured world to stare into the ocean unchanged since the time of the Lenape.

I figured I’d do it on the cheap—sleep in subways, spend the days in museums, write in jazz clubs by night. My mother got wind of the idea and called the police on me. The police of course informed her that I was over 18 and could do whatever I wanted to do.

My friends had more sense and convinced me that I should maybe stay in a hostel and not sleep in subways, so I stayed in a hostel in Harlem for a few days, and one of my J.C. Penney friends knew someone who was running a methadone recovery house in a Park Slope basement and invited me to stay there. The family was in-between clients at the time, so I slept in a dark room with no windows for several days, ate barbeque with the artist who owned the brownstone, and talked about poetry with her lesbian daughter (I’d never seen a parent embrace her gay child), and it was beautiful. I got drunk at night, told my J.C. Penney friend I dreamed of living in New York, and she told me that all my dreams would come true. They did.

Otherwise, I spent the trip wandering the streets of New York, sitting in museums writing about the art, journaling late night in jazz clubs, and basically having a glorious time—the kind of time one can only have when one is 20, not serious, and in love with the city. I sat in a stairwell in the Whitney and a man with a camera photographed me. I had no idea who Bill Cunningham was at the time. Could he have been Bill Cunningham? That’s what I love about New York. Everyone is pressed together so close, the known and unknown, lovers and enemies, people who came to nothing, people who came to everything, and they walk through the streets breathing in the same air once breathed by the Salingers and the Ferlinghettis.

I carried only two books with me: J.D. Salinger’s Catcher in the Rye and Lawrence Ferlinghetti’s A Coney Island of the Mind. I read them while riding the subway, or while sitting at the Lincoln Center trying to see angels in the fountain water.

I carried Ferlinghetti because he was, at the time, my idea of the ideal poet. He had written his way to the city, and then out west. He’d written himself a bookstore and a small press. He had written Allen Ginsberg into his life, and published his “Howl” and had gotten arrested for it. He’d written City Lights. He was what I hoped to be someday.

In Coney Island of the Mind, he compares modern humanity to the suffering humanity depicted in “Goya’s greatest scenes.” “We are the same people / only further from home / on freeways fifty lanes wide / on a concrete continent / spaced with bland billboards / illustrating imbecile illusions of happiness.” I read this and promised myself I would never embrace “imbecile illusions of happiness.”

Of course I went to Coney Island. My friend demanded it when she saw my copy of Lawrence Ferlinghetti’s Coney Island of the Mind in my bag. So we took a flask and rode all the way to Coney Island, staring at the city’s “drunk rooftops” marveling at “its trees full of mysteries / and its Sunday parks and speechless statues” its “surrealist landscape” of “protesting cathedrals.”

Coney Island was disappointing. We ate hot dogs, and stumbled drunk through the sand. We didn’t swim. It was too cold.

Lawrence Ferlinghetti’s Coney Island of the Mind is a marvel, especially as I sit re-reading it today, in the wake of Ferlinghetti’s death. Coney Island of the Mind, 5, is a stunning poem about the crucifixion, which seems to be written in the voice of a Black man (I keep hearing Baldwin’s fiction in the voice; I’m reading Another Country), except at the heart of the poem is a lynching, and therefore a commentary on the racist south. So of course it would be attacked as “blasphemous” by a New York congressman.

The New York Times has written a beautiful obituary of Ferlinghetti. Ferlinghetti wrote that a poem “should arise to ecstasy somewhere between speech and song.” The Times explains that when he opened City Lights bookstore, he made a point to take the books other booksellers ignored and to have it serve as a kind of salon for the city. And then he published Ginsberg’s “Howl” under his City Lights press.

He writes in Coney Island of the Mind, “I have not lain with beauty all my life.” And the lines are a beautiful commentary on the powerful tastemakers of art, those “art directors” who “choose the things or immortality.” Ferlinghetti writes he has not lived with that rarified sort, but “made a hungry scene or two / with beauty in my bed / and so spilled out another poem or two.”

He sees Chagall: “Don’t let that horse / eat that violin / cried Chagall’s mother / But he / kept right on / painting.” Coney Island of the Mind is Ferlinghetti’s manifesto, one he stuck to.

The poetry is haunted by the ghost of Arthur Rimbaud and Charles Baudelaire, with its “surrealist year” and its “surrealist landscape,” “and the mind its own illumination.” “Kafka’s Castle” “above the world.”

This is good stuff. This is poetry for the young. This is a poet falling in love with poetry and falling in love with language: “They pennycandystore beyond the El / where I first / fell in love.”

In time, Ferlinghetti became famous, but his early poetry has a radical tendency, not seeking after traditional acclaim. He writes: “Let us not wait for the write-up / on page one / of The New York Times Book Review … By the time they print your picture / in Life Magazine / you will have become a negative anyway.” Ferlinghetti was prescient.

I wrote poem after poem when I visited New York City that summer. I was still so young. There was still in me the sense of possibility of making great work, work that might change the world. I’m older now, and less sure. But Ferlinghetti reminds me why the work gets done. And it’s not for the Sunday write-up.

Ferlinghetti was always looking ahead. He saw Ginsberg before Ginsberg was the poet who wrote “Howl” and he made him the poet who had written “Howl.” He saw no place for poets to gather, so he made one. He saw no place for his friends’ poetry or books, so he made one. May I learn his life lesson well. And may we all someday “arise and go now / into the interior dark night / of the soul’s still bowery / and find ourselves anew / where subways and stall wait / under the River.”

About the Writer

Janice Greenwood is a writer, surfer, and poet. She holds an M.F.A. in poetry and creative writing from Columbia University.