Pema Chödron writes that “Spiritual awakening is frequently described as a journey to the top of a mountain.” The image of the spiritual awakening as a rarified experience that separates an awakened person from the rest of the world fails to adequately approximate what the old Buddhist masters would call a proper spiritual awakening. Spiritual awakening, for Chödron, who writes on ancient Buddhist tradition, is not a journey of transcendence, but a journey downward, into the pain and chaos of the world, towards the difficulty of connection, and the messiness of the world, not away from it.

And so these are the opening lines of Pema Chödron’s Comfortable with Uncertainty, an exquisite collection, where excerpts from longer meditations and books have been arranged like a ring of prayer beads. Pema Chödron is a teacher at Gampo Abbey in Nova Scotia. She practices the Shambhala Buddhist tradition that she studied under the tutelage of the master, Trungpa Rinpoche, who is credited as being among the first Buddhist monks to bring Buddhism to the West. In Comfortable with Uncertainty, 108 of Chödron’s most treasured writings have been collected to form what Emily Hilburn Sell describes as “a crystal bead with 108 facets, to be contemplated as you wish.” Buddhist monks often carry around a “rosary” with 108 beads, touching them as they pray. For those of us who happen to be less into fondling beads, and more into literary rituals, Comfortable with Uncertainty offers a practice more for the mind than for the hands. As an aside, I find it telling that in the first five drafts of this essay, I had mistakenly written the title to Chödron’s book as Uncomfortable with Uncertainty, as if my stubborn conscious mind would not admit the discomfort of uncertainty so readily.

It is easy to see the practice of meditation as a solipsistic act, a world-abnegating practice that drives its practitioners into deeper circles of navel gazing and self-indulgent isolation. I had my own doubts about how beneficial sitting still might be, given the veritable assault rifle of thoughts that passes through my conscious mind on a daily basis. Writers relish the non-sequitur of their own mindless chatter. The thought of trying to still my mind to pure thinking about thinking and refine even that down to nothing at all seemed to be antithetical to who I was as a writer.

And yet, I have found in my own practice the opposite has often proven to be true. In the quiet I sometimes find the most profound realizations of my life.

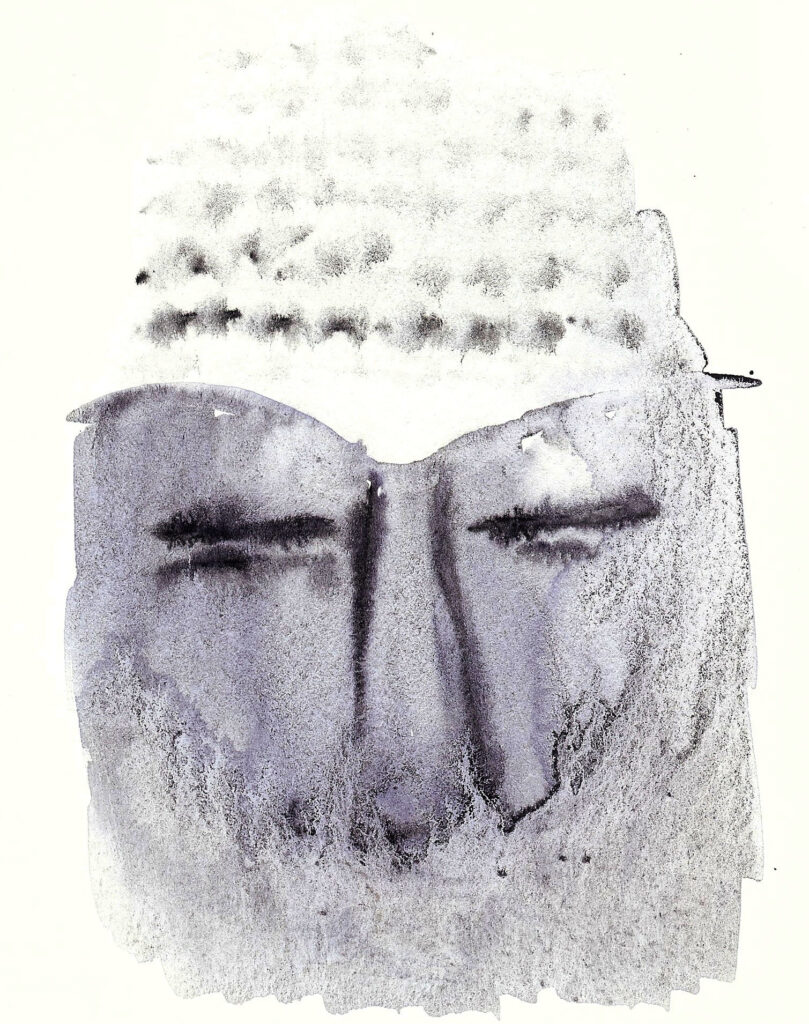

Just today I realized that the artistic act of mark-making carries with it not only the emotional state of the mark-maker in the act of making, but emotional states recalled. Only when the emotional state in the act of making aligns with emotion recollected in tranquility can the artistic process be complete.

I’m not alone in finding solace in meditation. It has become a marketing enterprise.

Just prior to the pandemic, boutique meditation studios opened up in cities like Los Angeles, New York, and Washington, D.C. promising practitioners beautified spaces in which to experience transcendence. These boutique meditation studios were forced to close during the pandemic, and many remain unopened, leaving the would-be meditators who would have been willing to spend hundreds of dollars a month for a particular kind of ambience to face themselves in the narrow confines of their own homes.

If I don’t count the times I meditated as a teenager and imagined myself transformed into a blade of grass, I have been meditating regularly for six years. The consciousness of youth is more permeable than the consciousness of adulthood, and I believe that we spend a great deal of money, alcohol, marijuana, and time trying to project ourselves back into those semi-permeable states. Notwithstanding my youthful attempts at meditation, the fact that I first began my serious adult meditation practice more recently highlights how much of my life has been characterized by doing something. I’ll admit that in the beginning of my adult meditation practice I felt incredibly stupid sitting on a meditation cushion. My life up to that point had been characterized by doing, by achievement. Always moving, I’d first gone to university, where my compulsive studying and ambition to get straight As kept me up all night, and then more ambition took me to Columbia University to study poetry. I wanted to walk in the footsteps of Federico Garcia Lorca. Then I was off to Canada, following love, and after that, I chased mountains, hoping to find transcendence literally at the top of cliffs.

Perhaps what is most revolutionary about the act of meditation is that it requires that a person do absolutely nothing for a period of time every day. In a world where our worth is derived from what we do, the choice to not do something, even for a little while, can feel extraordinary and not a little subversive. I admit that for a long time, I felt guilty, sitting down doing nothing. Even today, sometimes I still do.

The modern literature on spiritual awakenings is classified by what one does, the symptoms one experiences, as if spiritual awakening were another task of self-actualization to put on one’s vision board or another antidote to illness, if not illness itself.

For Chödron, spiritual awakening is not a single action, but a practice. Instead of transcending suffering, we inhabit it. We get humble. That is, we go down to the root of what humility means. Humble comes from the Latin word for humus, which means soil. Soil is a vibrant ecosystem of death and decay, as well as growth and life. It is a place where bacteria and fungus feed on corpses and where roots draw water and minerals into their cells, the petals of their flowers, the flesh of their fruit. It is the place where light captured in the pore of a leaf runs down into the ground, fusing the ecosystem beneath with energy and life. This process feeds us. It is what creates oak trees and apples.

Spiritual awakening is often characterized as the absence of pain and suffering. For Chödron, spiritual awakening is the exact opposite. It is the courageous act of choosing to embrace suffering. Transcendence comes through the passage through life’s difficulty, while making the choice to do so with generosity, patience, discipline, exertion, meditation, and finally, wisdom.

Comfortable with Uncertainty by Pema Chödron at Amazon.com (affiliate link)

Comfortable with Uncertainty by Pema Chödron at Bookshop.org (affiliate link)

About the Writer

Janice Greenwood is a writer, surfer, and poet. She holds an M.F.A. in poetry and creative writing from Columbia University.