When I moved to O’ahu I got it into my mind that maybe I’d learn to go spearfishing. There was something intrinsically beautiful to me about the idea of catching my own dinner, of literally putting food on the table. But now I’m not so sure. Fishing in O’ahu, for me at least, may remain only an idea. Each of us has our own boundaries regarding the eating of animals. For Jonathan Gold, eating a live prawn was too much. For me, I’m not so sure I should be eating animals at all, at least if I can’t bring myself to kill them myself.

Before I talk about how I got it into my mind to go fishing in O’ahu, I think it is important to note how my heart and body are constitutionally incapable of killing any living thing. I let my condo get infested with roaches before I finally relented and bought the good poison. (The good poison was so good that I put it into every gap in my kitchen counter, and didn’t expect it to work. Then, I went surfing for a couple of hours, and returned to a house covered in hundreds of roach carcasses. It was disgusting, and terrifying. I still don’t know what they put in that poison and I don’t want to know.

I (generally) never kill insects, even the annoying ones, like mosquitos. Despite this, I am not a vegetarian. I am full of contradictions. Mostly, if I go too long without protein, I become a very angry person and I don’t like being angry. If you don’t believe me, ask my ex-husband about being around me when we were vegan and traveling through Scotland. It wasn’t pretty. I distinctly recall storming away from a plate of vegetarian baked beans in some castle that had been turned into a hostel. Then again, I was starving, so I could have the memory all wrong.

In an attempt to save face and preserve my ability to claim myself a rational person, I decided that if I was going to eat fish, I might as well try to learn how to properly go fishing. I live in O’ahu, where the fishing is good (at least I imagine it to be). That’s how I found myself fishing in O’ahu with a friend.

More specifically, we had gone fishing in Kaneohe. The shallow bay is gorgeous, surrounded by the amphitheater of the Ko’olau Range. The turquoise blue water is so shallow and sandy on the bottom you can wade in waist deep water several miles out at sea. It’s a heartbreakingly beautiful place—a place where, I tell myself, I wouldn’t mind dying if I were a fish. My friend showed me how to cast and so I cast. He scanned the water for flashes of light, for birds.

For a long time, nothing happened. I kept casting and then snorkeled a bit, my heart calmed by the rhythm of the sea.

I was a young child when I saw a fish die for the first time.

My parents had driven my brothers and me to the Flamingo Visitor Center in Everglades National Park to see the sunset. Flamingo is located on the true tip of the Florida peninsula, the very bottom of the state. It is probably the closest place to Miami from which you can see the sunset (Miami, being on the east coast of the state, is only blessed with sunrises). With stiff legs from the long drive, we arrived at the visitor’s center. My parents took my hand and walked me to the sea wall. I must have been about five or six years old. That’s when I saw the fisherman pull the fish from the sea.

At first the fish didn’t appear to fight, and didn’t look much alive at all. The fisherman pulled the hook out of its mouth and dropped the fish onto the sidewalk, not far where my parents and I were sitting. That’s when it began thrashing around on the ground, clearly struggling.

“What’s happening to that fish?” I asked, alarmed, not really needing an answer from my parents to understand that the fish was suffering.

It continued to suffer, thrashing in the ache of its body, its gills opening and closing frantically like two gasping lips, unable to extract oxygen from the foreign element. What shocked my little girl brain the most was the way the fish leapt off the ground, using its strong tail fin to propel itself upward. It seemed to be fighting to find water.

“What is happening to that fish?” I pleaded, more panicked now.

My dad explained to me that the fish was dying, though I didn’t need an explanation. The animal was clearly dying.

That’s when I understood. The fish needed to be returned to the water. I also understood in that moment that all the fish we purchased at Long John Silvers and ate had also suffered a similar fate.

I ran to the fish and screamed at the man, told him to throw the fish back into the water. I cried, watching the fish’s frantic struggle grow weaker. The man did nothing. My father had to pick me up and carry me away.

That was the first time that I understood, viscerally, that animals we ate did not want to be eaten. At dinner that night, my mom handed me a bowl of shrimp. I asked my father if the shrimp had died, too. They had died. Up to that day, shrimp had been my favorite food. Now, I saw each one as a living thing that had suffered the same fate as that fish. I refused to eat anything that night. Though I didn’t become a vegetarian, I stopped eating shrimp, and still only rarely eat what used to be my favorite childhood food.

I have read a few pieces of writing in my life that have viscerally moved me (I think of American Psycho, and most online comments responding to anything written by a feminist writer), but no writing has turned my stomach quite like Jonathan Gold’s essay about eating a live prawn. The essay is mostly a boring takedown of a bad Korean restaurant. At first, Gold distracts himself from the bad food, by watching the prawns swimming around in a tank near his table. Later, when he realizes that everyone at the restaurant seems to be eating prawns, he decides to order the clear specialty. The waiter proceeds to dip “a hand into the tank, rippling the still, clear water until some of the prawns sprang up to nip at his fingers. He plucked the liveliest specimens from the water and brought them back to his station, where he quickly removed most of their shells.”

He goes on, “It was one of the most unsettling experiences I ever had in a restaurant, preparing to bite into a living creature as it glared back at me, antennae whipping in wild circles, legs churning, body contorting as if to power the spinnerets that had been so rudely ripped from its torso, less at that moment a foodstuff than a creature that clearly didn’t want to be eaten.”

While wading in the shallow bay, something finally bit. My friend had seen it from his boat, a silver flash in the water, and after casting a few times, he felt the line go taut. A few minutes later, he pulled the fish from the water.

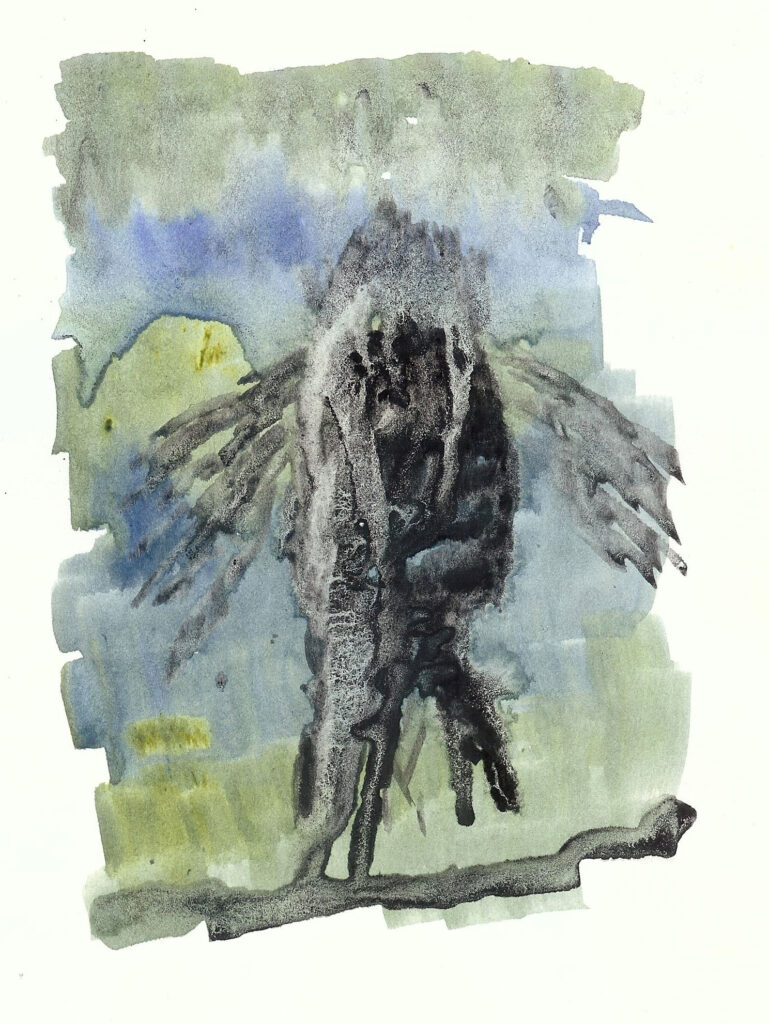

Like the fish from my childhood, it thrashed around in his hands, the body pure muscle, pure power. My friend is a good man, not one to allow a creature to suffer. He pulled out his fishing knife, put the fish down on the bottom of his boat, took a deep breath, hesitated for a moment, looked into its eyes, and then stabbed the fish right between them.

Surrounded by the mountains, the water as bright as blue ice, I reasoned that it wasn’t the worst place to die.

I crawled back into the boat and cried for the fish, the beautiful strong fish, all muscle and bone and eye, and life.

When I moved to O’ahu, I dreamed that maybe I’d learn how to spearfish and catch my own dinner. Now, I’m less sure about my ability. It’s a beautiful idea, but some things are better left dreams. Beauty in imagination can often turn ugly in practice. Think of every love affair ever had. Paolo and Francesca’s plight in Dante’s Inferno comes to mind.

So, I go foraging in the woods, pull breadfruit off trees, gather guavas. Maybe I’ll learn which ferns are edible. I try to keep a tomato plant in my lanai. The first one died, but the second one is doing okay, for now.

Jonathan Gold ate the prawn. “I bit into the animal, devouring all of its sweetness in one mouthful, and I felt the rush of life pass from its body into mine, the sudden relaxation of its feelers, the blankness I swear I could see overtaking its eyes. It was weird and primal and breathtakingly good, and I don’t want to do it again.”

I watched my friend kill the fish. I don’t know if I want to see another fish die.

About the Writer

Janice Greenwood is a writer, surfer, and poet. She holds an M.F.A. in poetry and creative writing from Columbia University.