The words in Clarity & Connection, Yung Pueblo’s second poetry book, often began as content on his widely popular Instagram account. His words are less poetry than popular self-help truisms, and he joins a growing number self-help content creators. Many of these content writers have qualifications: they are lawyers or psychologists sharing their expertise in a popular format. In fact, as a creator of legal content writing, I see these creators as offering new insight into how the medium of Instagram can be used to reach a wider audience. One example is Erika Kullberg (@erikankullberg), a corporate lawyer with 4.3 million Instagram followers who gives pretty good advice on how to get airline companies to pay for your delayed bags. Dr. Nicole LePera (@the.holistic.psychologist) is a psychologist with 6.1 million followers who writes about how attachment styles can impact your current relationships.

Yet, the practitioners of self-help poetry are seldom psychologists or therapists, and seldom have professional training as social workers. They are often young.

This is not to say that youth doesn’t have its wisdom. After all, Taylor Swift knew everything she needed to know when she was 16, and can now spend the rest of her career re-recording her teenage songs to perfection. She’ll be fine and so will we.

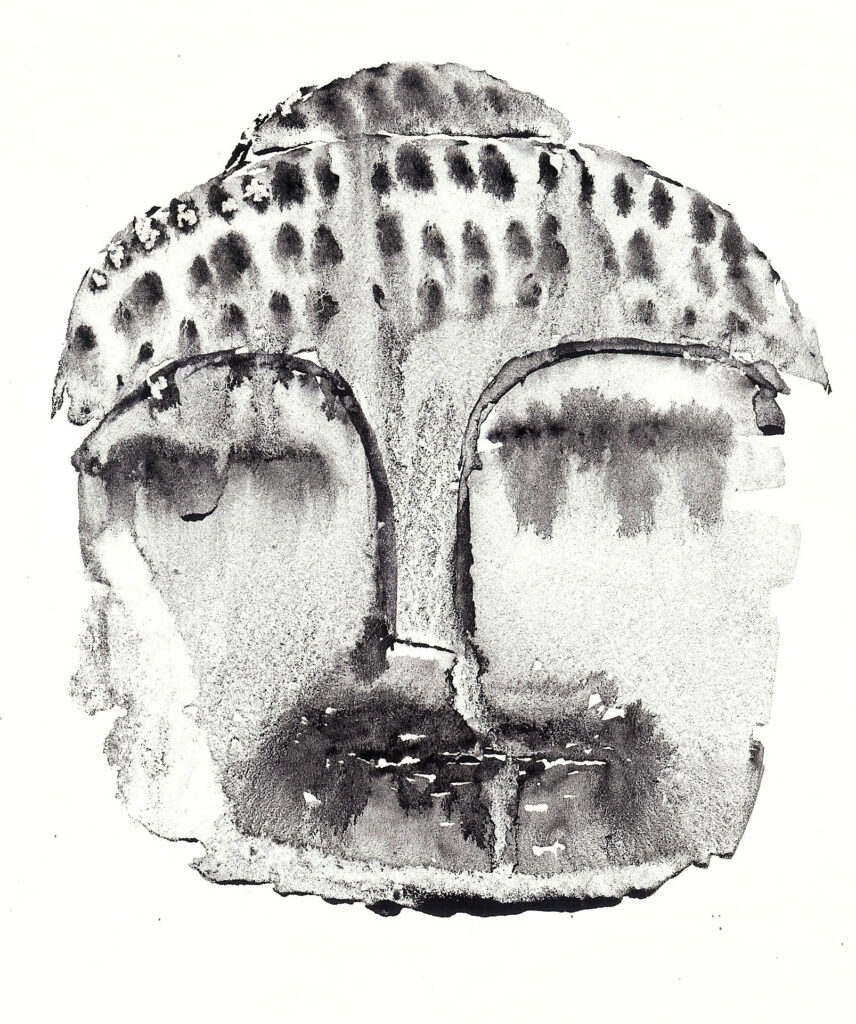

The dangers of writing self-help content or offering forth wisdom too early in your expertise is that it is all too easy to be vague, all too convenient to render truth in platitudes. What makes the best poetry helpful is the ruthlessness of its specificity. I think here of Sylvia Plath’s collected poems and Dante Alighieri’s rigorous and specific assessment of all the ways love can go wrong in the Divine Comedy. Han Shan’s Cold Mountain poems offer a Buddhist perspective, but are so specific that the philosophy shimmers beneath, a philosophy of doing, not preaching.

In Clarity & Connection, there is some clarity and some connection, but not a great deal of specificity. Philosophy overtakes the poetry, leaving little room for poetic expression. There’s no subtlety.

Pueblo writes: “the biggest shift in your life happens when you go inward… with time, intention, and good healing practices, / the past loses its power over your life.”

What exactly are these “good healing practices?” What exactly does “inward” bring?

The poems that follow don’t offer much of an answer. We are reminded to “help people, but have boundaries.” Lest we fear we are falling into our old patterns, Pueblo offers the sage advice that “repeating the past / is a sign of progress.”

At worst, self-help spirals into the icy circle of hell that is pure cliché, and Pueblo’s poetry is often a frozen lake of these. Pueblo writes straight-faced about “the fruits of your labor” having an “immensely positive / impact on your life.” And later Pueblo writes: “we do not need to reinvent the wheel.” Poetry is the antithesis of cliché; it’s disappointing to see so much of it here.

What I fear is that this poetry is offering a kind of roadmap for young people trying to figure out their lives, but the roadmap is so cliché and well-worn as to be useless. I don’t see Pueblo’s personal perspective at all. When I was young, I turned to Arthur Rimbaud, Sylvia Plath, Mary Karr, Toni Morrison, Charles Simic, Oscar Wilde, Louisa May Alcott, Lois Lowry, J.D. Salinger, and some Stephen King. The benefit of turning to a chorus of voices who offer guidance in their specificity is that there is seldom the danger that you’ll take one perspective too seriously. Yes, I wanted to bad like Rimbaud, and I wanted to be angry and sad like Plath, and I wanted to be sexy like Karr, deep and rooted like Morrison, surreal like Simic, witty like Wilde, a feminist like Alcott, a visionary like Lowry, honest like Salinger, and scary like King, but because each was so unique it was impossible to model my writing or my intentions too precisely on any one of them.

Pueblo’s prescriptiveness is so pervasive in Clarity & Connection that it is almost pathological. It is too easy to see the roadmap—so easy as to be useless at best, or dangerous at worst. Is it really true that we “should not trust” the way we see ourselves when our “mood is down?” I’m not so sure. Can’t pain also be instructive?

Pueblo’s thesis is basically this: know thyself. Turn inward, face emotions, embrace your difficult parts because there is no relationship that can be had unless one first has a strong relationship with oneself. It’s not terrible advice, but it can get terribly repetitive.

Some of these pieces read like journal entries written after the writer read something enlightening. For example there’s one piece that summarizes the Buddha’s teachings on craving: “attachment is also when you try to place restrictions on the unexpected and natural movements of reality.” I don’t see a poetic reprocessing of the raw material into art, though. There’s this line from another poem, “a mind full of attachments craves the fulfillment of its yearnings and attempts to mold the world into the shape it desires.” There are moments inspired by Pema Chödrön, which are virtual paraphrases, and there are poems that dissipate into a cloud of New Age smoke: “the world is a giant pool of moving vibrations…when we cultivate out minds, / we cleanse our personal vibe.”

In many ways, these pieces read like half-formed essays. For example, Pueblo follows up his discussion of craving with this: “it is important to note that there is a substantial difference between craving and having goals or preferences.” What follows is a half-formed interrogation of attachment which paradoxically privileges attachment to happiness. Nuance isn’t Pueblo’s strong suit. These investigations of philosophical and Buddhist thought could have been better served with more time and artistry. There’s a whole section on attachment and relationships that show all the excitement of a writer delving into Buddhist thought. But unlike writers like Jane Hirshfield who subject their philosophy to poetic transformations, the material here remains quite raw.

The sad thing about Clarity & Connection is that it could have been a far better poetry book if it had just been edited down and made much shorter, and if the writer had taken more time with the work. Hidden within the fluff are some moments of illumination. I was struck by the simplicity of a poem that arrives early in the book and could have easily been the opening poem: “do what is right for you / do it over and over again.” Those two lines remind me of Seamus Heaney praising the poetry of Han Shan: “There is no path / that goes all the way—enviable stuff, / unfussy and believable.” Isn’t this the goal of all poets—to write “enviable stuff / unfussy and believable?” With those two lines Yung Pueblo hits a high note, one worthy of opening a book. Enviable stuff.

A patient reader is sometimes rewarded. Buried at the end of another poem is this: “if i build a home within myself, a palace of peace created with my own awareness and love, this can be the refuge i have always been seeking.” Simple. Yes. But also beautiful. If Pueblo were a skilled poet, he’d find another image to yoke to this, like Hafiz could do, and really have something to work with. Here’s another: “a clear mission / does not always have a clear path.” And here’s another: “when we travel inward, we may hit a particularly rocky layer of the mind, a sediment of conditioning that has been thickly reinforced.”

The moments of genuine wisdom in this collection arrive almost accidentally, and seemingly unknown to the writer himself. There are some exceptions; Pueblo seems aware that his insight, “we need to make compassion structural” is important if only because he chooses to put it in italics.

Ultimately, though, these moments were unfortunately few and far between. I often found myself distracted while reading this book, in the same way I find myself distracted when an often repeated commercial comes on the radio. I’ve heard so many of these themes before. “Inner work” and the urge to go “inward” are not new ideas, and they haven’t quite been refined into art in Yung Pueblo’s Clarity & Connection. If you’re looking for self-help, or for poetry, there are other books where you’ll find it better done.

Strong content writing is the distraction. But what happens when we are distracted from the distraction?

About the Writer

Janice Greenwood is a writer, surfer, and poet. She holds an M.F.A. in poetry and creative writing from Columbia University.