The Pearl Poem is one of the most beautiful of all the medieval poems, and quite possibly one of the most beautiful elegies ever written.

The second of the Buddha’s four noble truths is that attachment leads to suffering. Lion’s Roar, a Buddhist magazine explains: “We suffer, and make others suffer, when we try to hold onto things after their time, whether it’s relationships, experiences, or just the previous moment… Nonattachment is neither indifference nor self-denial. Ironically, letting go of attachment is the secret to really enjoying life and loving others. It is freedom.”

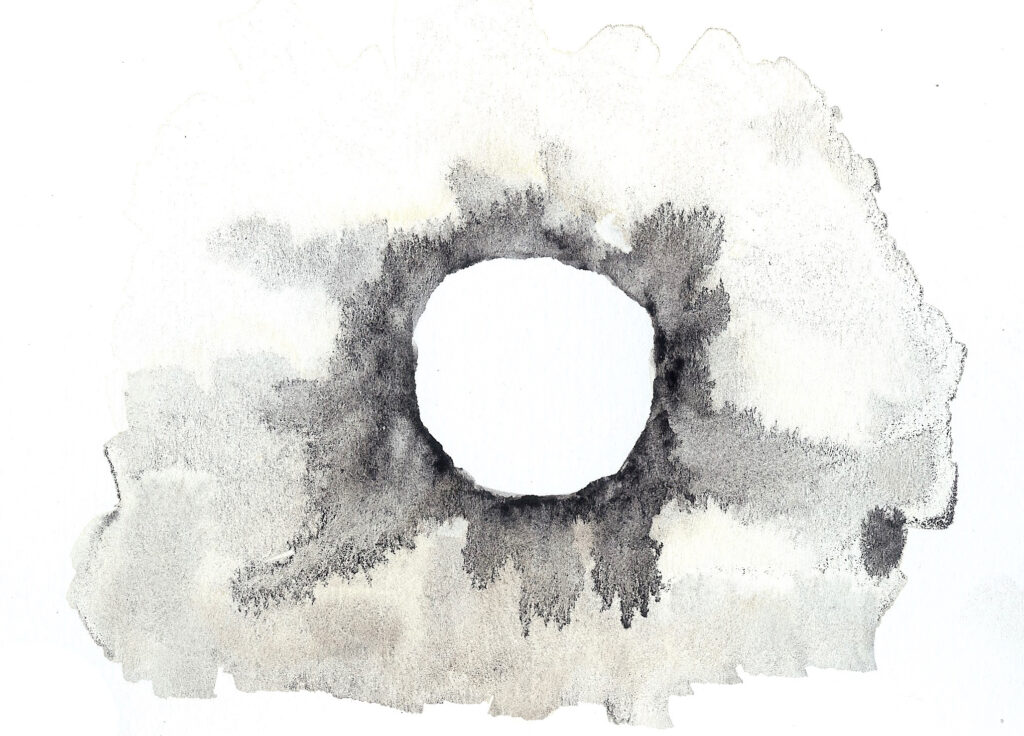

While Buddhist thought offers wisdom for those striving for nonattachment, medieval thinkers also offer some fascinating insights into nonattachment. The medieval Pearl poem, for example, is an intricate meditation on loss, death, nonattachment, release, and purification. This stunning allegory on loss and redemption is considered by many scholars to be one of the most intricate poems in middle English and possibly one of the most intricate poems ever written. 101 stanzas each have their own rhyme scheme and are linked together by a single word that echoes in the stanza that follows. The poem is tied together to form a ring because the last linking word connects the reader back to the first stanza. The poem is an allegory, a dream vision, and a meditative journey with no beginning and no end. Like a jewel, its internal reflections and refractions are manifold. For the purposes of this essay, I’m relying on William Vantuono’s Pearl translation.

The poem opens with the speaker having lost his “special pearl without a spot.” The first movement of the poem ends with the speaker mourning over the grave of the dead girl, clinging to the earth and stench of decay. In fact, the stench is the thing that renders the speaker unconscious. The poem begins in the fundament, on solid earth. One imagines a man digging up a grave hoping to unearth the past, but finding only decay and “odor to my head then shot” that begins the dream vision to follow.

The speaker then ascends into space, into a world so beautiful “Tapestries never were found in a heap/ of half so dear an adornment.” The landscape the speaker encounters is a place of pure adornment. The repetition of the word “adornment” is critical. The vision is a spiritual one. The beauty presented to the speaker is merely décor to guide the spirit towards the lessons it needs to learn. The poet takes pains to de-emphasize the importance of the décor, while simultaneously drawing the reader into a realm so beautiful. Ultimately, the reader is admonished, with each repetition of “adornment” to let go of clinging, to appreciate the vision, but to let it pass through, like a stream. The visual feast presented to the speaker is illusory, an act of accommodation to human senses, because the spirit world is not physical.

After wandering through the vision world, describing its more splendid wonders, the speaker finally encounters a maiden bedecked in pearls. He asks the maiden: “Are you my pearl whose loss I lamented?” The maiden explains to the speaker that he is mistaken to think his pearl is lost. She is not lost, but safely treasured away in the realm of the spirit. Furthermore, the maiden admonishes the speaker for his attachment. She explains:

“Now, gentle jeweler, if you shall lose

Your joy for a gem that from you veered,

You apply your mind to maddening views,

And trouble yourself with transience bleared.”

The maiden reminds the speaker that it is madness to cling to things of a transient nature. Instead, he is urged to place his heart and hope on things that are eternal and unchanging.

“You have called fate thief, and feared,

When it has shown you something surer.”

And to the speaker, “each gentle word a jewel without flaws.” Language is the pearl. The poem is the pearl. The dream vision is the pearl. The maiden is the pearl. Nothing is not the pearl. Everything is the pearl. And the poem is connected, and so all things are connected, if you follow them to their source, which is love, spirit, heart, the breath that moves the sun and other stars.

But the speaker remains mistaken because he decides he will stay in the vision with his pearl. “I shall dwell with it in sheer woodshaws.”

And yet, the speaker is mistaken. The maiden explains:

“You say you believe I exist in this scene

Because your eyes have lit on me.

Second, you say in this country

You from me shall never sever.

The third, to cross this stream you see

Cannot now be, joyful jeweler.”

And so, the speaker is reminded that it is only with the heart that one sees rightly and that the scene he thinks he sees does not exist. Furthermore, he cannot cross the stream, because he is yet alive. In order to cross the stream “Your corpse to clot must coldly cleave.” The maiden reminds the jeweler that calling God cruel for this would not make him “stay… one step from his plan.”

Ultimately, we are each constrained by fate, but the realm of the spirit is not constrained by temporal things.

And so, we are subject to our fate, but have a choice in how we submit to it. We can choose to submit to our fate with joy and bliss or in despair and grief. Yes, the poem continues with all its Christian imagery and hope for eternal salvation. But for me, the core of the poem is in the lesson it offers earlier, the lesson of choice, of illusion, of nonattachment. We will lose things in this long and difficult life. We will not get them back. Or they will come back in another form, but never the same. Ultimately, our job is to not attach ourselves to each blessing, but to take it in for the adornment it is, and to accept the lessons love passes our way. The choice in life is the choice to live in illusion, or to see the connected invisible soul beneath.

About the Writer

Janice Greenwood is a writer, surfer, and poet. She holds an M.F.A. in poetry and creative writing from Columbia University.