The influence of Rupi Kaur can be seen all over Amanda Lovelace’s debut poetry book the princess saves herself in this one. The use of epigrammatic form devolves often into cliché and the terrible use of enjambment are just the beginning of the similarities. Lovelace and Kaur also walk similar poetic trails: writing on the themes of sexual assault, menstruation, trauma, self-harm, and more.

Trigger Warning: the book contains a “trigger warning.”

Yet, Lovelace does something that Kaur does not do, which is to take a single theme and trope and push it to its limits. Lovelace explores and explodes the trope of the fairy tale. If you were a little girl raised on Disney fairy tale princesses, this book of poetry is for you.

Lovelace is still young enough to believe in the fairy tale ending. As a creator of legal content writing for law firms, I know all too well where that fairy tale ending often ends. Someday someone brilliant will write the next chapter of all our fairy tales: the Cinderella who wants a separation because she wants more for her life than to be a princess stuck in a castle, the Beauty who finally gets the restraining order against the abusive beast, the Ariel who wants a divorce so she can return to the sea because she realizes no man is worth losing your voice or identity over.

Facetiousness aside, Lovelace’s poetry book asks an essential question. How much has the fairy tale princess and the fairy tale itself shaped the female psyche? Lovelace’s speaker is obsessed with books and has transformed her life into a story. Anyone with even a mildly literary imagination can fall victim to this.

But there’s a danger in trying to transform life into a story. Lovelace explores this in one of the early poems in the book: “life—/the thing/ that happens to us/ while we’re off / somewhere else… wishing / ourselves into / the pages of / our favorite / fairy tales.”

Unlike Kaur’s poetry, which I think could use an editor, some of Lovelace’s poems read as more mature, complete, and well-rounded. (This doesn’t mean that Lovelace couldn’t also benefit from a stronger editorial eye.) The simple fairy tale trope is doing the majority of the heavy lifting. When Lovelace pulls it off, the poems work because the fairy tale theme and subject matter create multiple levels of meaning. The poems are at their best when the literal theme subverts the fairy tale theme.

The fairy tale theme is a unifying force that adds additional layers to poems that would otherwise be one-note. Yet, this is still the work of an immature poet. The poems that subvert and interrogate the fairy tale princess theme are few and far between, and too many of the poems simply fall into cliché.

Let’s start with the good news. Lovelace’s poem about parental abuse is brilliant. “The queen,” the speaker’s mother, offers the “princess” sugar, but instead, the sugar is salt. This clever conceit sounds very “Princess and the Pea,” but it carries the weight of allegory. The poem lands well (I can maybe forgive the terrible enjambment): “this is what abuse is: / knowing you are / going to get salt / but hoping for sugar / for nineteen years.”

The monsters hiding under the princess’s bed become the boys waiting to tell lies. The ghosts in the room are not ghosts but the haunting memories of sexual assault.

There are moments where better editorial insight might have made the book stronger. There are poems that shouldn’t be in the book at all (some poems work best on Instagram, where many of these pieces first saw the light of day). For example, Lovelace’s poems about social media are sometimes adequate, but work best in the more disposable form of social media. Better yet, they could have been saved for another poetry book written about the perils of social media.

The poems about weight and weight loss could have been better integrated into the fairy tale theme. Lovelace misses an opportunity with these that I believe a stronger, or more experienced poet may not have missed.

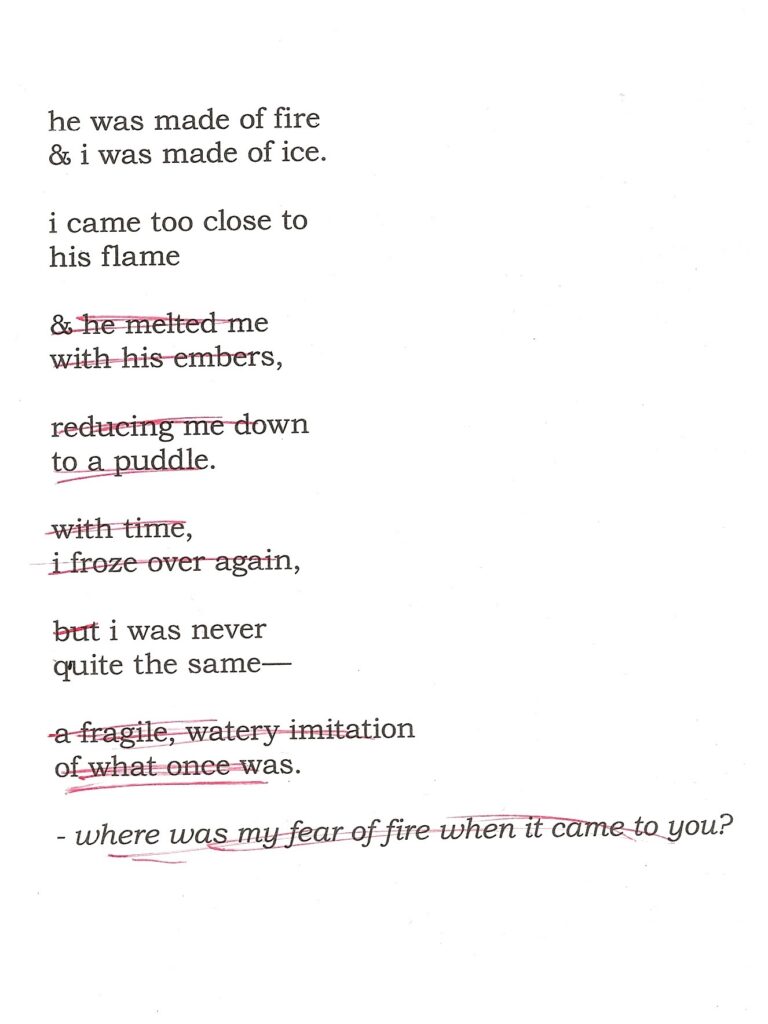

Lovelace’s parody of Robert Frost’s “Fire and Ice” is almost good—I took the time to distill it down to its essence. The poem could be reduced to three stanzas, pack more punch, and still convey the same general idea. If Lovelace had been a fellow student in one of my Columbia University M.F.A. workshops, this is what I would have suggested for her poem:

And yet, within the haystack of this too-long book, there are beautiful needles looped with the finest of threads. The poem where the speaker finds the dead body of a loved one is stunning. The speaker finds the body with a “mouth opened/wide enough/to suck all the oxygen/from the room,/wide enough/to plant lilies in.” I wouldn’t change a word here.

If fairy tale is the use of melodrama to narrative effect, too many of the poems become merely melodramatic because they fail to transform or harness the thematic. The fairy tale is rife with clichés, and using this to structure your entire poetry book is a risky move. If it is not handled in a manner that transforms the material, it comes across as a crutch. You can’t use the fairy tale as a way to disguise cliché, it just comes across as cliché.

I think the most disappointing thing about the book is that it fails to live up to its promise and its title. Maybe the princess saves herself in her own rationalization, but this isn’t a fairy tale without its prince charming.

And so the book ends with the cliché. The prince is real. He comes and saves the princess, despite the title of the book. The latter half of the book reads like a bunch of really bad pop songs. The boy replaces everything. “my boy/he is even/better than/books.” If the princess turned her life into a book and books saved her in the opening sequence, by the latter part of this poetry book, the prince has arrived and resolved the need for books and stories altogether.

And what does a modern princess do once she’s escaped the tower and found her prince charming? Why, she moves to New York, of course. The last section of the book is a weird medley. A person jumps in front of the speaker’s subway train and the speaker memorializes her in a poem (no mention of Anna Karenina, sadly). A man on the street asks the speaker to help him find lost photos. Caught in the millennial rat race, the speaker writes about “working minimum wage jobs/ with college degrees.” But the poems don’t go deeper than this and fail to comment on the conditions of injustice, or social and racial inequity that got us here to begin with.

The conceit of the fairy tale gets lost in the real world, and Lovelace’s strengths are in the conceit.

About the Writer

Janice Greenwood is a writer, surfer, and poet. She holds an M.F.A. in poetry and creative writing from Columbia University.