I have to admit that I missed Rupi Kaur. By this, I mean that I had so fully committed to retreating from the New York poetry scene and from the poetry and literary scene in general that I didn’t even notice it when a book of poetry made the New York Times bestseller’s list. I was busy working as a legal content writer, climbing cliffs in Yosemite, and rebuilding my life after divorce.

If you, like me, have been hiding under a rock, Rupi Kaur first made her name on Instagram, where she gained a following of loyal fans (she currently has 3.9 million Instagram followers). She’s grouped within a movement in poetry known as the “Instapoets.” On Instagram, where the currency is “followers” and “likes,” Rupi Kaur leads a pack of other popular poets that include Cleo Wade (over half a million followers), Atticus (1.4 million followers), and R.H. Sin (1.8 million followers). The pendulum of commercial success always brings its share of backlash on the backswing. And Kaur has seen the run of it.

Priya Khaira-Hanks, writing for the Guardian notes that “Kaur treads a fine line between accessibility and over-simplicity and often stumbles into the latter.”

I can’t blame the critics. It is easy to dismiss Kaur’s poetry books as doggerel. And I agree that her simplicity can often be banal. She most often markets in generalities, revels in cliche, works in shock value, peddles in platitudes, and her use of the epigrammatic form does for poetry what stock photos have done for photography. Critics have noted the over-simplicity of her style, with some even questioning whether her work should be called poetry at all.

The word poetry is derived from the Greek word, for “making.” In this context, the conscientious making of language is poetry. We can debate whether Kaur’s work is good poetry, but we cannot dispute that she is working within the poetic form. Kaur, like many other Instagram poets, is a maker.

Kaur’s ability to harness the medium of Instagram has created a genre of poetry of its own. To ignore a writer who has done this would be a mistake. Her language is concentrated and it evokes an emotional response in its audience—as her millions of followers will attest. Work by women is often devalued or seen as frivolous and these views are never stronger than when a woman is writing about feminism, her vagina, or women’s issues.

Kaur cannot be ignored if we are going to have a real discussion about what modern poetry is, and what it can be. Kaur’s biggest problem is that she lacks a good editor.

My Rupi Kaur Poetry Edits

In my work as a legal content writer, I am often called upon to edit law firms’ landing pages, blogs, and articles. Part of the process of receiving an MFA in poetry involves editing the work of other poets and writers for homework and in class. I couldn’t help but find myself editing Kaur’s work as I read.

Kaur’s Milk and Honey is a poetry book at its best when the writer is the most specific and the most vulnerable. There are moments when the arrangement of words juxtaposed to her doodles achieves something close to artistry.

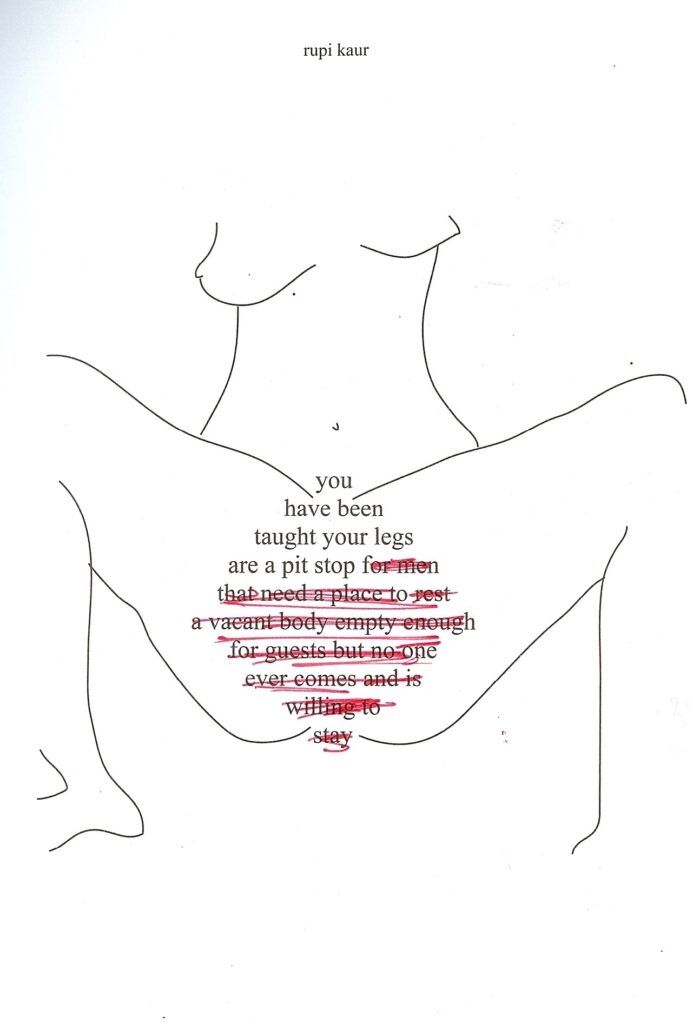

Take for example, this piece:

Despite her brevity, Kaur still lacks full control of her poetic powers. The entire second half of this poem is redundant. A pit stop is an apt enough metaphor to describe a place “empty enough/ for guests but no one/ever comes and is/willing to/stay.” The reader, even an Instagram audience, possibly drunk at 2 a.m. can be trusted to get the point.

And yet, for its flaws, the drawing, along with the placement of the words, succeeds. It is important to note that Kaur received wide media attention when Instagram removed pictures of her in bed menstruating. The vagina is either vilified or sexualized; I have not often seen it textualized. Kaur’s replacement of the vagina with words is brilliant. After all, words are the potent vacancy of sound not yet sounded—spaces of meaning into which the patriarchy has ascribed so much meaning. The undepicted vagina becomes a generative space. The vagina has a voice. The decision to not depict the vagina is an act of resistance against objectification, and it is also a move that controls the meaning of that which is not depicted.

A major aspect of Kaur’s project is the act of reclaiming body as her own. She writes, “the next time he/ points out the/ hair on your legs is/ growing back remind/ that boy your body/is not his home.” And the poem would have done well enough to end there…but it doesn’t. Kaur’s inability to self-edit results in other regrettable pieces as well.

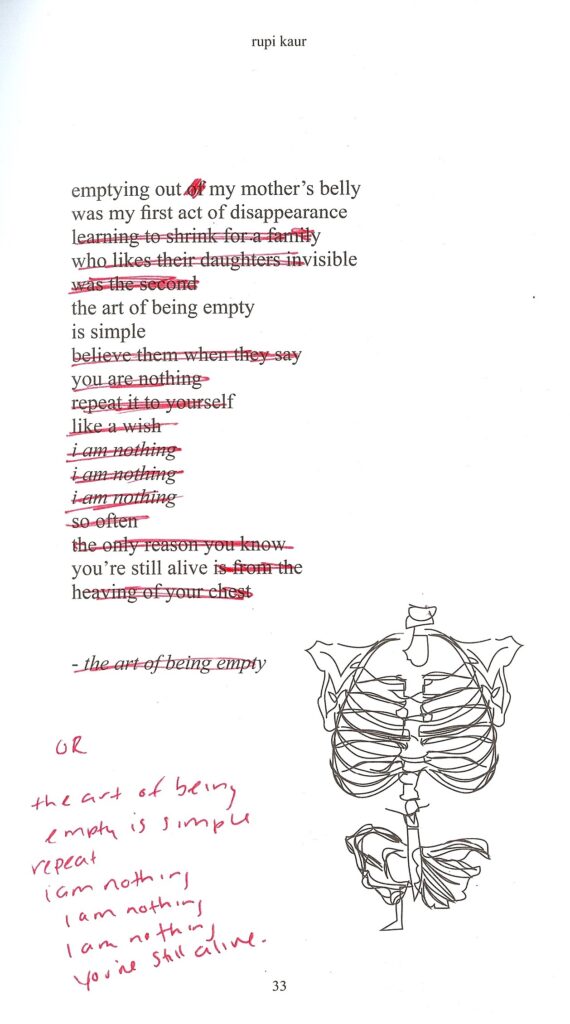

Kaur writes, “the art of being empty/ is simple.” This gorgeous couplet, given Kaur’s use of brevity and white space would be enough. Instead, Kaur goes on, with unfortunate results. Here’s my suggestion:

Kaur addresses topics of love, sex, female representation, relationships, and also darker topics, like parental abuse and rape. Kaur is at her best when she is most specific. In this way, she is the true heir of the confessional poets, following the footsteps of Sylvia Plath and Anne Sexton, except more simply and with less artifice. I can most accept Kaur if I take her for what she is. We have young adult books for young adults and now we have a young adult poetry whose primary platform is Instagram. This is beautiful.

Her poetry book is weakest when her tendency to overgeneralize, combined with her brevity, results in throwaway poems that would have been best left out of the book. The work is hardly poetry at all in some places, reading more like an adolescent journal opened for the world to see. It’s a fine line between writing poetry for adolescents and writing juvenilia yourself. Again, this is where an apt editor might have been able to help Kaur. Her book could have been half as long and much better.

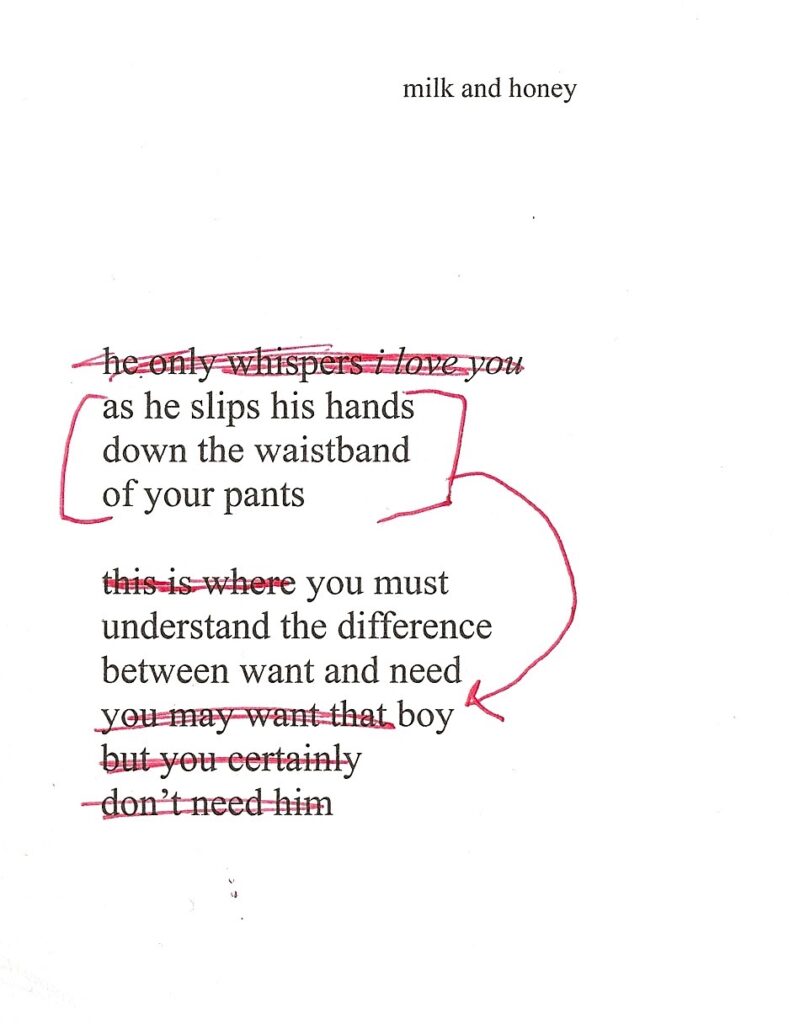

And I feel this way about many of the poems. Take for instance this one:

I rather love the boldness here, but it is blunted by the exposition. Invert the stanzas and cut out the exposition and you have something closer to poetry.

When Kaur boldly depicts female sexuality, it easy to remember that the poetic cannon offers so few instances of female sexuality so openly represented. There are times where Kaur’s condensed poetry reminds me a little of Sappho.

Still, I do not want to place Kaur in the cannon. Kaur in a minor poet with a large following. Here, I find it important to note that John Greenleaf Whittier was a quite popular poet in the 1850s, but the poet we remember today is the “no-name” Emily Dickinson of the same era. I cannot guess what posterity will make of Rupi Kaur, but I can tell you what I make of her now. She has captured the imaginations of an audience of young women, and she has done so deftly. She serves as a gateway for her readers to find other poets and to tap into their own poetic potential.

And that’s the thing about Kaur. She has potential. She has an audience. In the September 2006 issue of Poetry Magazine, John Barr wrote: “Poetry in this country is ready for something new.” Why has establishment poetry fallen on hard times? Why are Instagram poets flourishing?

Establishment poets attend MFAs (like I did). Establishment poets write their first poetry book manuscripts with the intention to submit these manuscripts to first poetry book contests where the manuscripts are read by judges. Those who submit to the contests often tend to only submit work they think might be selected by the judge (I know I didn’t submit to contests where I feared the judge didn’t share my aesthetic). When crafting a poetry book manuscript, these academic poets might only include poems that have been published in literary journals, or may only include poems that could potentially appear in literary journals; work that appeals to a common denominator. The poetry world is not a place for risk-taking any more. And that’s why I admire Kaur—her audacity to post her poetry, her words, on Instagram—a medium meant for art and photography; a social medium (of all places); her boldness in writing honestly about her life; her bravery in self-publishing her own work. And maybe Kaur’s most important comment on modern poetry today is this: poetry, in order to succeed and reach people must be social.

Kaur takes her poems outside academia and into the conversations her audience is having. Her audience cares about sex, breakups, relationships, and taking ownership of their own bodies. They care about female experience told unfiltered. Her audience cares about seeing a woman write about real life in a meaningful way. For centuries poets have been walking the fine tightrope between the vulgar and the rarified view. Shakespeare did it. Dante did it too. Too often contemporary academic poetry is so rarified as to slip off the face of the earth. Contemporary poets would be wise to put a little dirt in their shoes.

Barr wrote in 2006 that he didn’t know what the next thing in poetry will be. Now we know what it is. Instagram poetry. Twitter poetry. Establishment poets can deny its ascendency all they want and criticize it away, but it won’t make it go away, and it won’t make sales go down.

Kaur is writing for an audience of young women who are heartbroken, lonely, and who are learning how to navigate the vicissitudes of love and self-determination in a world for which there are few artistic precedents. When I was a teenager, I fell in love with Arthur Rimbaud’s poetry for its edginess, for its willingness to depict sexuality and for its contempt for modern life without filter. The voice I found in Rimbaud was from another era, but was still one with whom I could relate.

I love that Kaur is writing in the face of the establishment. This is why she is successful. Despite my reservations about her as a poet, I am interested in where she will take her work next.

I only wonder what poetry and art she would produce if she holed herself away for a few years, read more poetry, and worked with a capable editor on a new poetry book (and I’m not talking about The Sun and Her Flowers). With her reach, wit, and ability, she perhaps really could change the poetry world—and maybe not just in sales and followers. I’m actually looking forward to Home Body, a book she appears to have written while in quarantine. UPDATE: I’ve reviewed it here.

About the Writer

Janice Greenwood is a writer, surfer, and poet. She holds an M.F.A. in poetry and creative writing from Columbia University.